Mind the Gap - the Persistence of Gender and Health Inequalities

In 2019 the British Heart Foundation (BHF) released a briefing on clinical findings that women in England and Wales had worse health outcomes following heart attacks than their male counterparts. This, the BHF stated, was due in part to a public perception that heart attacks are predominantly a male condition. This, combined with unconscious biases in the delivery of healthcare led to delayed treatment and weaker chances of survival among female patients.

This triggered a flurry of press attention, with article headings such as “Women die of heart attacks as men get best treatment” (The Times, 30.9.19) focussing on disparities in diagnosis and treatment, and women not receiving the same standard of treatment and care as men.

I felt that an important issue was being missed, one that might contribute to improvements in female diagnosis and prompt care, and ultimately better health outcomes. Health literacy (the ability/capacity to obtain, communicate, process, and understand basic health information and services in order to make appropriate health decisions) is pivotal to disease prevention and timely care seeking. However, in the UK, the misperceptions surrounding heart attack symptoms persist: we commonly consider symptoms of left arm and chest pain to indicate heart attack; and this is the case for many men. However, female heart attack symptoms of back and jaw pain and throat discomfort are not well known, and if better understood, might empower the population to raise the alarm for women sufferers to receive urgent medical care and reduce the case fatalities.

Having done my bit to raise awareness by writing to The Times (31.9.19), in the course of my work as a health and social development adviser, I reviewed the global situation of inequalities in health between women and men. Disparities are apparent across all regions of the world and global health outcomes and mortality patterns are due in part to biological differences between male and female growth patterns, biochemistry, metabolism and hormones throughout the life cycle, in addition to women’s risks associated with pregnancy, unsafe abortion and childbirth. The 2019 Global Burden of Disease, a comprehensive study of causes of death and disease, reveals that, world-wide, men disproportionately suffer a greater number of years of ill-health, disability and early death (disability-adjusted life years) than women.

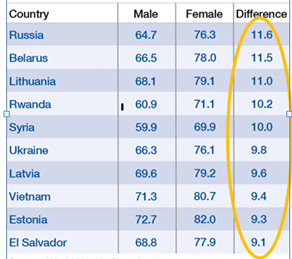

Analyses of government, non-government and even some academic research data do not always include sex-disaggregation. However, where it has been carried out, the relationship between sex, gender and health becomes visible. One of the clearest indicators of inequalities between male and female health is the gap of 4.6 years in life expectancy, with women outliving men in many country contexts. The extract from the 2018 Global Health 50/50 Report, shows that in some countries, disparity is as high as 11.6 years (as shown in the chart on the right), indicating that combined gender and biological issues can have a substantial impact on mortality.

Analyses of government, non-government and even some academic research data do not always include sex-disaggregation. However, where it has been carried out, the relationship between sex, gender and health becomes visible. One of the clearest indicators of inequalities between male and female health is the gap of 4.6 years in life expectancy, with women outliving men in many country contexts. The extract from the 2018 Global Health 50/50 Report, shows that in some countries, disparity is as high as 11.6 years (as shown in the chart on the right), indicating that combined gender and biological issues can have a substantial impact on mortality.

Biological factors, however, only account for some of the disparities in health such as sex-specific causes of ill-health and premature death, such as prostate and testicular cancers in men and cervical and ovarian cancers in women. According to the 50/50 Report, gender- the socio-cultural constructs surrounding biological sex - is among the most significant determinants of health.

Gender is considered to influence health and well-being across three domains:

- Through its interaction with the social, economic and commercial determinants of health.

- The health behaviours that are protective of, or detrimental to health outcomes.

- In the modes by which health systems and services respond to gender, including how they affect the financing of and access to quality health care, including treatment by health care providers.

In many societies male behaviour is detrimental to health outcomes where men are more reluctant than women to seek medical assistance. This is especially true for intimate or sexual symptoms, which can worsen health outcomes due to delays in diagnosis and treatment. Women on the other hand, might have greater experience of discussing health issues with care providers through their history with maternity services, and be less likely to delay health care seeking due to embarrassment. These influences can be seen in the significant gender differences following curative rectal cancer surgery, with women experiencing significantly longer survival than their male counterparts. This may relate to better post-surgery self-care in women, who are more likely to flag potentially embarrassing symptoms problems at an early stage. Men on the other hand, are less likely and later in seeking additional care for intimate problems and as a result, their health outcomes can be compromised.

“ Gender - the socio-cultural constructs surrounding biological sex - is among the most significant determinants of health. ” - The 50/50 Report

The interaction between sex, gender and health is complex, especially as it intersects with and amplifies other drivers of inequities that compound effects on health and well-being. The extent to which socio-cultural contexts exclude girls from school, restrict female travel outside the household and participation in wider public life, affects female knowledge about health issues, illness prevention and where to obtain treatment and care. It is estimated that today, 63% of illiterate adults are women and that a gender bias persists in access to education, whereby girls are 1.5 times more likely than boys to be denied their right to primary school education. Female education has multiple direct and indirect influences on health: women with secondary education earn twice as much as those without it, enabling them to better provide for their children, and, better-educated women marry later, when they are physically more prepared to support pregnancy, child birth and motherhood. They also have fewer unplanned pregnancies, which is associated with better child care, nutrition and health for fewer children.

The common subordination of women in many societies is associated with a distinction between roles of men and women and their assignment within domestic and public spheres. This has multiple negative impacts, not only on girls and women themselves, but also on their abilities as mothers to optimally care for their children as there is positive relationship between female school attendance, the empowerment of women in the household and the nutritional status of their children.

In many societies, gender norms dictate that men control the household income and access to cash. My research in rural southern Tajikistan highlights, for example, how the low status of daughters-in-law within their patrilineal households means that they have little access to cash, as paid work is deemed to be inappropriate for women. As their husbands have become reliant on migrant labour in Russia in recent years, newly-married women and young mothers have been placed in a position where they have to seek both the permission and cash support from their parents-in-law. This hampers women seeking gynaecological, family planning and other health services and at the same time constrains them in seeking timely care for their children. The gendered constructs surrounding women means that they have no autonomy or decision-making power over their own health or that of their children.

Men also suffer culturally-determined health inequalities. In certain settings, they are more likely to be exposed to infectious disease, for example malaria transmitted by mosquitoes in the course of employment in forestry, construction or mining in the tropics. Where women are excluded from factory work, there is gender disparity in non-communicable diseases as men have higher risk of exposure to industrial pollutants and toxins, leading to higher rates of associated cancers.

Disparities in gender and health are exacerbated overall in times of instability, emergency and crisis. Working in Nepal at different points during the civil war (1996 to 2006) I was aware that some of the most empowered and advantaged young women in urban areas were shamed and abused at security checkpoints if they were discovered to have contraception pills or condoms in their handbags. This discouraged them from carrying essential commodities to prevent unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections. In the same way, female rights are frequently compromised during the process of migration. As the state of crisis surrounding human movement increases, so does the infringement of the right to health, access to services and the risk of bodily harm. In heightened conflict, sexual assault is frequently used as a weapon and method of intimidation. While perpetrators are in the main men against women, males may also be assaulted and because of embedded psycho-social aspects of masculinities, they are less able to seek help, and services are less enabled to provide appropriate care and treatment.

To avoid preventable illness and premature mortality resulting from gender blindness in the health sector, we must routinely and meaningfully conduct disaggregated analyses of the data we collect. This will not only reveal unmet health needs, but inform our health policy, programming and approaches to deliver optimal health outcomes, equity and inclusion, in different country settings around the world. Shaped and maintained by social, cultural and religious institutions, gender concepts can be changed and shift over time. Institutions such as government, academia, the health and development sectors, as well as cultural and religious organisations have the power to initiate change and be very effective partners for gender-transformative action. Those of us working as health, education and development practitioners and researchers can design our programming and protocols with a gender lens to ensure that information and interventions are fully inclusive to ensure the best health outcomes for women, men, girls, and boys.

Dr Kate Molesworth (1985, Human Biology) is Health and Social Development Adviser at the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, University of Basel. She is also a member of our SJC Women's Network Steering Group. If you would be interested in contributing a piece for a future edition of the SJC Women's Network eNewsletter, please email women@sjc.ox.ac.uk.

Check for updates on the Women's Network Facebook Page