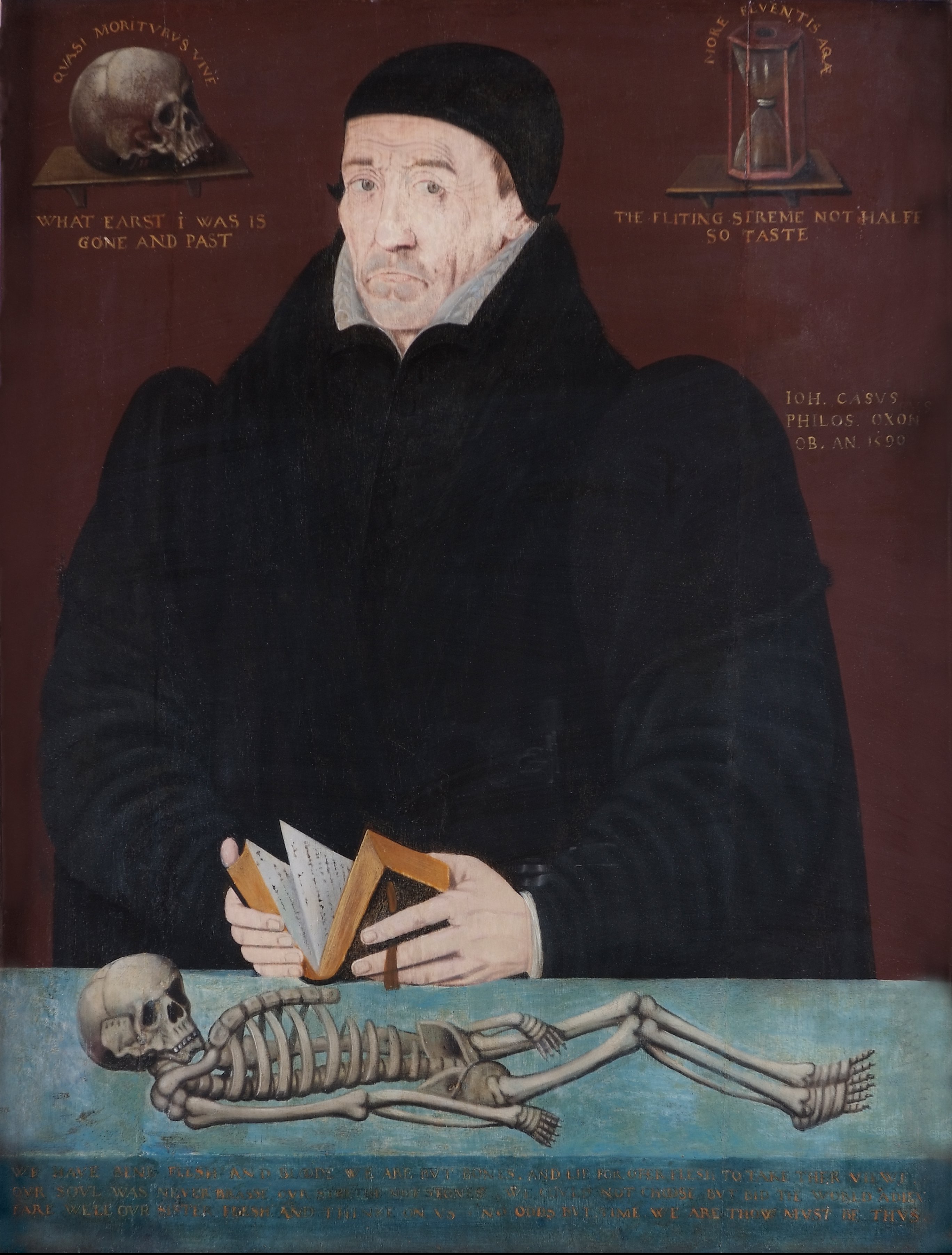

18. Portrait of John Case, by an unknown artist

John Case, unknown artist, H 89.5 x W 68.6 cm, oil on panel

John Case, unknown artist, H 89.5 x W 68.6 cm, oil on panel

Why are portraits so important to us? The number

of portrait images that fill the walls of Oxford colleges attest to their significance

as a form of communal commemoration - of academic achievement, of political, societal

or religious importance, and of financial sponsorship. But why do we

particularly value records of our physical likeness to represent these

qualities to future audiences?

The St John's

portrait of John Case, the Aristotelean writer and physician, provides a window

into the motivations for commissioning a portrait in the late sixteenth

century, at a time when painted depictions of the academic and professional

classes were becoming increasingly popular. The c. 1590 portrait has

been a familiar and somewhat spooky sight in the Hall since the mid-nineteenth

century. When situated in their sixteenth-century context, the painting's rich

symbolism and numerous inscriptions reveal the enduring role of the body in memory

and commemoration.

John Case matriculated

as a scholar at St John's in 1564, at the age of nineteen. He became a Fellow and,

after being compelled to marry the local widow to whom he had been paying

visits, he was forced to leave his position at the College. He subsequently

worked as a tutor of logic and philosophy for the University and his teaching

was greatly admired. Case later completed medical degrees and practiced as a

physician. He wrote extensively on Aristotelean thought, and was highly regarded

for his scholarship.

Case's

half-length portrait on panel certainly echoes this reputation, representing

him as a serious and scholarly figure, in cap and gown. The props, such as the

book and the small skeleton, have occasionally been suggested to connect to Case's

medical practice and interests in anatomy. However, developments in our understanding

of the portraiture of this period reveal the significance of additions like the

skull and the hourglass. Art historian Tarnya Cooper highlights John Case's personal

interest in pictorial representation. In a 1598 preface he provided for a treatise

on painting translated by Richard Haydocke, he argues that portraits act as 'a

kind of preservative against Death and Mortality: by a perpetuall preserving of

their shapes'. This connection between portraiture and mortality situates

Case's own portrait in the genre of memento mori portraiture. Another

example of memento mori portraiture in the Hall is the portrait of Sir

William Paddy, with a pocket watch marking time. The inscriptions on Case's

portrait further reflect this preoccupation with death: 'QVASI MORITVRVS VIVE'

(Live as if you are about to die), 'MORE FLVENTIS AQÆ' (Like flowing water), 'WHAT

EARST I WAS IS GONE AND PAST / THE FLITING STREME NOT HALFE SO FASTE', and a

further longer inscription on the table in front of him.

By

contrasting his living form with death in this portrait painted during his

life, Case emphasises, in spite of his life's achievements, the mutable and

transient nature of the human body, reflecting late sixteenth-century attitudes

to salvation and the afterlife. However, his funerary monument, installed in St

John's' chapel by his wife, son-in-law, and associates is inscribed with an

epitaph containing a similar sentiment: 'CASUS IN OCCASUM VERGIT, VIVITQUE

SEPULTUS', which has been translated as 'Case inclines to his setting and lives

in his grave.' As commemorative artefacts after the death of the subject, these

paintings and sculptures were seen as more than inactive wall decoration. What

was, in life, a personal reflection on mortality becomes an example of it,

giving a poignancy to the sitter's hope of eternal salvation. In the viewer's

act of looking at the painting and reading its inscriptions, it becomes a means

for Case to have a life after life, his piety living through our collective

memory. Next time you are in the Hall, I urge you to pause for a moment and pay

Case's portrait above the high table a visit.

View the painting on Art UK here.

Anna Clark is a second year DPhil student at St John's College. She works in collaboration with the National Portrait Gallery researching the histories and afterlives of portraits of early modern female patrons in Oxford and Cambridge Colleges.

Anna Clark is a second year DPhil student at St John's College. She works in collaboration with the National Portrait Gallery researching the histories and afterlives of portraits of early modern female patrons in Oxford and Cambridge Colleges.