Celebrating Eleanor Coade: Georgian Craftswoman and Entrepreneur

Eleanor Coade

Eleanor Coade was born in 1733, the elder daughter of a Baptist wool merchant in Exeter. By her early thirties, Eleanor had established herself as an independent businesswoman in the City of London, working as a linen draper. While the linen trade had more female business owners than other industries, most of these women were wives or widows continuing their husbands’ businesses. This was not the case for Eleanor. Though widely referred to by the courtesy title, ‘Mrs Coade’, Eleanor never married, recognising the business value of remaining a femme sole a century before the Married Women’s Property Act (1882) allowed married women control over their money and property.

An 1804 view of Eleanor Coade’s Lambeth manufactory. London Metropolitan Archives

An 1804 view of Eleanor Coade’s Lambeth manufactory. London Metropolitan Archives

After her father died in 1769, Eleanor changed industries, taking over a struggling artificial stone manufactory at Narrow Wall, Lambeth: now the site of the Southbank Centre. Within a few years of the takeover, Eleanor sacked the manufactory’s manager, Daniel Pincot, after he falsely represented himself as the sole proprietor of the factory. Writing in the Daily Advertiser on 11 September 1771, Eleanor asserted her authority:

Whereas Mr Daniel Pincot has been represented as a Partner in the Manufactory which has been conducted by him; Eleanor Coade, the real Proprietor, finds it proper to inform the Publick that the said Mr Pincot has no Proprietry in this Affair; and that no Contracts or Agreements, Purchases and Receipts, will be allowed by her unless signed or assented to by herself

The yard at Eleanor Coade’s Lambeth manufactory, c. 1804. London Metropolitan Archives

The yard at Eleanor Coade’s Lambeth manufactory, c. 1804. London Metropolitan Archives

When Eleanor took over the Lambeth artificial stone manufactory, British manufacturers and architects had spent decades searching for an effective artificial stone formula, experimenting with various ceramic compositions and firing techniques. It was a ubiquitous and rivalrous industry, with competitors continually trying to discredit one another’s products and methods. It is all the more remarkable, then, that Eleanor was able to establish a near-monopoly in the artificial stone market by the end of the 1780s. As the Landmark Trust's historian, Caroline Stanford puts it, 'Eleanor's success lay in positioning and promoting her product so that it became actively preferred to natural stone for durability, price, and reliability of execution'.

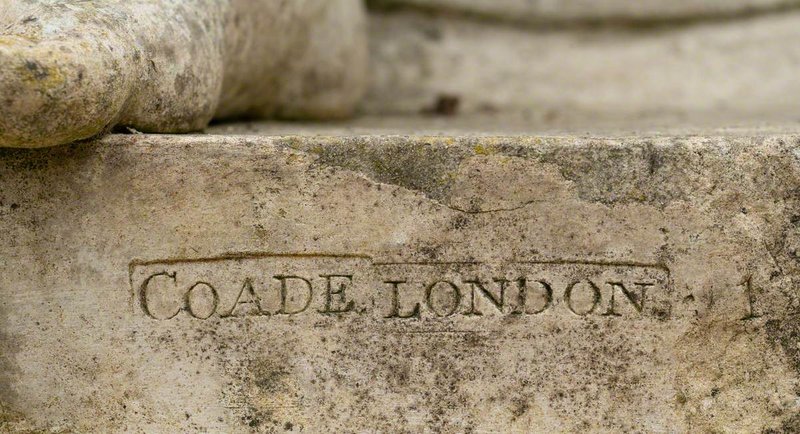

‘Coade stone’ (as Eleanor branded it) was prized by architects and clients for its close resemblance to natural stone and its peculiarly hard-wearing properties. Indeed, extant Coade stone sculptures and monuments have proved so resistant to weathering and erosion that many remain in pristine condition over two hundred years after their original manufacture. The quality of Coade stone is such that stone restoration experts have recently tried to recreate Eleanor’s ceramic material for modern masonry repair – see this 2015 article in the Financial Times for details.

The Immortality of Nelson (Nelson Pediment), King William Courtyard, Greenwich. Image credit: Andy Smith/ Art UK

The Immortality of Nelson (Nelson Pediment), King William Courtyard, Greenwich. Image credit: Andy Smith/ Art UK

Besides being exceptionally durable and weatherproof, the Coade stone formula was also remarkably malleable and versatile, giving Eleanor’s manufactory a distinct advantage over its competitors. These properties made Coade stone the go-to choice for a broad range of applications, from architectural details, to commemorative and funerary monuments, fonts, statues, busts, coats of arms, chimney-pieces, garden ornaments, and furniture. Some of Eleanor’s most famous work was carried out by royal appointment to George III and George IV, for whom she constructed Coade stone additions to St George’s Chapel, Windsor, and the Royal Pavilion, Brighton. Eleanor was also commissioned by public subscription to construct a memorial for Lord Nelson at Greenwich Hospital in 1810 – the forty-foot-wide pediment is often considered her greatest work, taking several years for the now eighty-year-old managing director to complete.

Eleanor’s pre-eminence in the artificial stone industry was undoubtedly boosted by her collaborations with prominent Georgian architects and sculptors, such as John Bacon, Thomas Banks, John Flaxman, John Nash, Joseph Panzetta, Sir John Soane, and James Wyatt. (Wyatt incorporated Coade stone into his design for the Radcliffe Observatory, Oxford: see below.) Eleanor’s relationships with such skilled craftsmen and artists only increased the desirability of Coade stone throughout Georgian Britain.

The 'Evening Panel' at the Radcliffe Observatory, Oxford, depicting Nyx (the night) with Artemis (Goddess of the moon) setting off for the night’s journey.

The 'Evening Panel' at the Radcliffe Observatory, Oxford, depicting Nyx (the night) with Artemis (Goddess of the moon) setting off for the night’s journey.

When Eleanor died in November 1821, she made significant bequests to the Girls’ Charity School in Walworth and to numerous women in her immediate circle in both London and Lyme Regis. Many were spinsters and widows, but she also left three unusual bequests to married women. In contrast to usual practice, Eleanor stipulated that her female legatees were to sign for the bequests themselves and that their husbands had no right to their legacies.

The Coade manufactory continued for only a short time after Eleanor’s death, finally closing in c. 1840. Whilst there is no memorial to Eleanor, the legacy of her business endures in the hundreds of surviving examples of Coade stone across the British Isles and beyond, from St John’s College, Oxford, to the zoo in Rio de Janeiro!

Farnese Flora

The manufacture of statues in the likeness of Roman gods and goddesses was a stock in trade for the Coade Artificial Stone Manufactory. As the goddess of flowers, Flora was a particularly popular garden ornamentation, and Eleanor Coade was commissioned to create at least four statutes of Flora during her lifetime.

Farnese Flora at St John's College, Oxford. Pictured with the College President, Professor Lady Sue Black.

Farnese Flora at St John's College, Oxford. Pictured with the College President, Professor Lady Sue Black.

The Coade stone Flora at St John’s is a copy of an eleven-foot marble statue owned by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, one of the earliest and most significant collectors of Greco-Roman antiquities. The original Farnese Flora can now be found at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples (see above). Many versions of this statue have been reproduced in different materials, and it is believed that Eleanor’s Farnese Flora was based on a 1782 engraving of the marble original by the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi. The exact date of St John’s acquisition of Coade’s Farnese Flora remains unclear, but it is likely to have been part of the College’s collection since the early nineteenth century. Today, the statue stands in the President’s Garden.

In 2020, St John’s Flora was the subject of a brilliant web piece by then-DPhil History of Art candidate Rachel Coombes. Reflecting on the statue, Dr Coombes wrote

The goddess of flowering plants and the spring season holds in her left hand what looks like an empty cornucopia, as if in anticipation of its being filled with the fruits of springtime blossoming. The elaborate folds of her drapery, cascading from her raised left arm and rhythmically gathered up in her other, demonstrate the ease with which Coade stone could be moulded for the modelling of complex forms. The figure assumes the relaxed but dynamic contrapposto pose (with her body weight bearing down on one foot), so favoured by Ancient Greek and Roman sculptors. Coade has exaggerated the pose to suggest forward motion, as if to emphasise the goddess’s vivacity.

You can find further details of St John’s Farnese Flora on Art UK by clicking here.

Further Reading:

Alison Kelly, 'Coade, Eleanor (1733-1821)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online)

Alison Kelly, Mrs Coade's Stone (Upton-upon-Severn: The Self Publishing Association Ltd in conjunction with The Georgian Group, 1990)

Caroline Stanford, 'Revisiting the Origins of Coade Stone', The Georgian Group Journal, 24 (2016): 95-116. (Online)

Caroline Stanford, 'The Peculiar Mrs Coade', (2022) YouTube.