On this day – 464 years ago

May was an important month in the foundation of St. John’s.

There is plenty of evidence that Sir Thomas White had been planning the

founding of the College for several years, but it was in May 1555 that the

College first took form. On the first day

of May, White secured from Queen Mary and King Philip (it is often forgotten

that Philip II of Spain who launched the Armada against Elizabeth I had also briefly

been King Philip of England when married to Elizabeth’s half-sister Mary)

permission to found a college. This was done in the form of a charter known as

Letters Patent (so called because they were issued open rather than closed), which by the mid-sixteenth century had developed into a large parchment

document, illustrated with a picture of the monarch enthroned in the initial

letter, with the Great Seal of England attached to its base.

May was an important month in the foundation of St. John’s.

There is plenty of evidence that Sir Thomas White had been planning the

founding of the College for several years, but it was in May 1555 that the

College first took form. On the first day

of May, White secured from Queen Mary and King Philip (it is often forgotten

that Philip II of Spain who launched the Armada against Elizabeth I had also briefly

been King Philip of England when married to Elizabeth’s half-sister Mary)

permission to found a college. This was done in the form of a charter known as

Letters Patent (so called because they were issued open rather than closed), which by the mid-sixteenth century had developed into a large parchment

document, illustrated with a picture of the monarch enthroned in the initial

letter, with the Great Seal of England attached to its base.

By this time White had already chosen a site for St. John’s,

having apparently seen the site in a dream before coming to Oxford and

identifying it. This was the site of what had been St. Bernard’s College, a

college for Cistercian monks. Like all other monastic institutions in England

St. Bernard’s had been dissolved by Henry VIII about fifteen years earlier and then later he had given it to Christ Church

when he had refounded Cardinal Wolsey’s college in 1546. By a deed dated 25 May, the Dean and Chapter of Christ Church sold White the site of what the deed

calls Bernerde Colledge in return for a rent of 20 shillings a year and a promise that

if St. John’s could not find one of their own fellows suitable to be President

then it would be a student of Christ Church (this has happened just once and,

of course, no longer applies!).

By this time White had already chosen a site for St. John’s,

having apparently seen the site in a dream before coming to Oxford and

identifying it. This was the site of what had been St. Bernard’s College, a

college for Cistercian monks. Like all other monastic institutions in England

St. Bernard’s had been dissolved by Henry VIII about fifteen years earlier and then later he had given it to Christ Church

when he had refounded Cardinal Wolsey’s college in 1546. By a deed dated 25 May, the Dean and Chapter of Christ Church sold White the site of what the deed

calls Bernerde Colledge in return for a rent of 20 shillings a year and a promise that

if St. John’s could not find one of their own fellows suitable to be President

then it would be a student of Christ Church (this has happened just once and,

of course, no longer applies!).

Just four days later Sir Thomas issued a charter of his own,

which has become known as the First Foundation Deed. It was made on 29 May 1555

and was both signed by White and had his own personal seal appended to it. It

formally created the College, in a strictly legal sense, by conveying all the

properties that the founder had acquired as the College’s endowment (mostly in

south Oxfordshire and north Berkshire to the west of Abingdon) to five men: the

first President, Alexander Belsyre, and four other scholars, of whom two would

be amongst the first fellows of the College. In fact, it was to be another two

years before the College actually opened as a functioning institution on 24

June (the festival of St. John the Baptist) 1557, but this deed created the

College as a legal corporation and was no doubt done in order to protect the

nascent College’s endowment in case the founder should die before the

foundation of the College was complete.

Just four days later Sir Thomas issued a charter of his own,

which has become known as the First Foundation Deed. It was made on 29 May 1555

and was both signed by White and had his own personal seal appended to it. It

formally created the College, in a strictly legal sense, by conveying all the

properties that the founder had acquired as the College’s endowment (mostly in

south Oxfordshire and north Berkshire to the west of Abingdon) to five men: the

first President, Alexander Belsyre, and four other scholars, of whom two would

be amongst the first fellows of the College. In fact, it was to be another two

years before the College actually opened as a functioning institution on 24

June (the festival of St. John the Baptist) 1557, but this deed created the

College as a legal corporation and was no doubt done in order to protect the

nascent College’s endowment in case the founder should die before the

foundation of the College was complete.

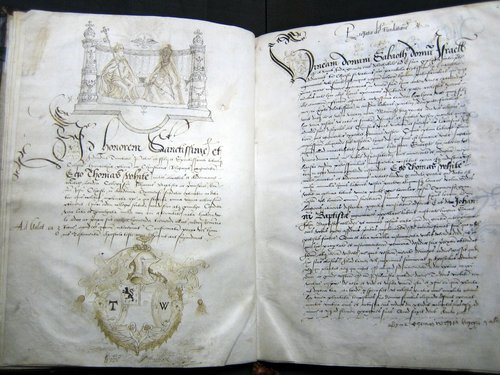

In fact, Sir Thomas White survived not only to see the

College actually open its doors in 1557, but for another ten years, which was

enough time to see through one last act in the foundation of St. John’s, again

in May, though in 1562. The previous year, White had been one of the key movers

in the foundation of another major educational institution, the Merchant

Taylors’ School in London. So, on 14 May 1562 he officially rewrote

the statutes of St. John’s, now incorporating the rule that at least 37 of the

50 fellowships were to be reserved for alumni of the School. An official copy

was made by John Bereblock, a fellow of the College, with a beautiful drawing

on the title page which has been variously interpreted as the Holy Trinity, as

Philip and Mary, or as Elizabeth and John the Baptist. It is probably intended

to be ambiguous in what by 1562 was a largely crypto-Catholic college in the

emerging Elizabethan Protestant Church. Sir Thomas White signed every page of

Bereblock’s copy.

In fact, Sir Thomas White survived not only to see the

College actually open its doors in 1557, but for another ten years, which was

enough time to see through one last act in the foundation of St. John’s, again

in May, though in 1562. The previous year, White had been one of the key movers

in the foundation of another major educational institution, the Merchant

Taylors’ School in London. So, on 14 May 1562 he officially rewrote

the statutes of St. John’s, now incorporating the rule that at least 37 of the

50 fellowships were to be reserved for alumni of the School. An official copy

was made by John Bereblock, a fellow of the College, with a beautiful drawing

on the title page which has been variously interpreted as the Holy Trinity, as

Philip and Mary, or as Elizabeth and John the Baptist. It is probably intended

to be ambiguous in what by 1562 was a largely crypto-Catholic college in the

emerging Elizabethan Protestant Church. Sir Thomas White signed every page of

Bereblock’s copy.

These statutes were destined to last almost three hundred years, until arguably a new foundation of the College took place when a royal commission insisted on rewriting the statutes of all the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge. St. John’s, a deeply conservative college at that time, resisted and had new statutes forced upon it in 1861, just a year short of three centuries after Sir Thomas White had signed his statutes into law. To be strictly accurate, it was a little under a year and a month short of three hundred years, as the Victorian statutes passed into law in April, not May.