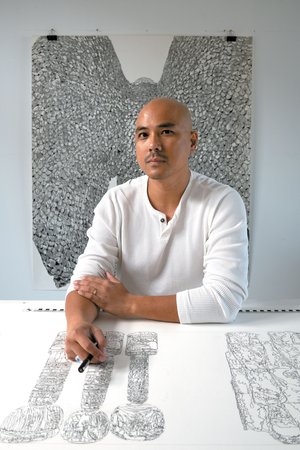

Pio Abad and 'Prince Giolo'

‘To Those Sitting in Darkness’ is an exhibition of new works by the artist Pio Abad at the Ashmolean Museum until 8 September 2024.

Abad’s work concerns colonial history and cultural loss and is deeply informed by world history, with a particular focus on the Philippines, where he was born and raised in an academic family who campaigned for justice in the 1970s and 80s. Abad’s poetic, personal and political art offers a powerful critique of the way many museums collect, display and interpret the objects they hold and questions prevailing perceptions and perspectives.

Now based in London, Abad has created a wide-ranging body of work for 'To Those Sitting in Darkness' including drawings, sculptures and text. The title is a reference to American writer Mark Twain’s satire To the Person Sitting in Darkness (1901), which strongly criticised imperialism.

The exhibition explores, identifies and illuminates objects Abad found in the rich and varied collections of the University of Oxford, focusing on those where their histories have been marginalised, unexplained, ignored or forgotten. His intricately detailed creations are displayed together with other artists’ work alongside ‘diasporic’ objects researched and chosen by Abad from a range of Oxford institutions’ collections and archives.

Abad was particularly inspired by a drawing he found in the Musæum Pointerianum (MS 253) from the St John’s Library special collections. The drawing shows ‘Prince Giolo’, a tattooed Filipino slave who was brought to Oxford in the 1680s and exhibited as an exotic curiosity in pubs and other venues. In ‘Giolo’s Lament,’ Abad re-renders Giolo’s tattooed hand through eleven engravings on marble arranged on the gallery's walls, a moving reminder of his fragile humanity.

‘Prince Giolo’ in the Musæum Pointerianum (St John’s College, MS 253)

This illustrated engraving from the St John’s collections is part of an advertisement campaign promoting the exhibition of the so-called ‘Painted Prince Giolo’ in 1692. The etching was made by John Savage (fl. 1683–1701), who also worked as an engraver for The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society from 1683. The text underneath refers to ‘Prince Giolo’, or rather his tattooed skin in particular, primarily as a commodity. At the same time, all sorts of romanticised stories circulated about him as part of the marketing campaign. The engraving is now part of the Musæum Pointerianum, an album or scrapbook of so-called ‘curiosities’ collected by the antiquary John Pointer (1668–1754), which contains further materials relating to how this Asian man was treated by English colonialists and unscrupulous businessmen.

The available details of the story of the Philippine islander Jeoly (c. 1662–93/4), who became popularly known as ‘The Painted Prince’ or ‘Prince Giolo’, are confusing and sometimes contradictory.

Jeoly was captured together with his mother by slave traders and they were both bought by the English explorer, pirate, and privateer William Dampier (1651–1715), possibly around 1686 (Barnes, p. 34). Dampier is today known as the first person to have explored parts of Australia and the first man to have circumnavigated the globe three times. In 1709, he rescued Alexander Selkirk, who served as the inspiration for Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. Sometime after his purchase of Jeoly and his mother, Dampier went bankrupt because his quest to discover unexploited sources of spices and gold had been unsuccessful. In 1691, he returned to England with his notebooks and Jeoly. Jeoly’s mother had previously died in Dampier’s captivity. In England, Dampier sold Jeoly and later published the notebooks describing his travels, including his version of Jeoly’s story, as A New Voyage around the World (1697). Jeoly was exhibited in London for the financial profit of his new captors.

Another item in Pointer’s album is a printed leaflet repeating the text of the engraving with some additions and ending with the following announcement:

" He will appear publiquly [sic] every day from Nine in the Morning to Twelf at Noon, and from Three in the Afternoon til Six or Seven in the Evening. But if any Persons of Quality, Gentlemen or Ladies, do desire to see this noble Person at their own Houses, or any other convenient place, in or about this City of London; they are desired to send timely notice, and he will be ready to wait upon them in a coach or chair, any time they please to appoint, if in the day time. Vivant Rex & Regina. "

It is believed that the public display took place at the Blue Boar’s Head Inn in Fleet Street in June 1692 (Angel). This advertisement makes it seem as if Jeoly presented himself voluntarily to be marvelled at by the Londoners when in truth he was forced to be gawk at as a dehumanised ‘exotic curiosity’.

Not long after his exhibition in London, Jeoly died of smallpox in Oxford in or shortly after 1692. It is not quite clear why he was in Oxford. Perhaps his health had already been failing when he was presented by the Oxford Orientalist and Bodleian Librarian as an object for his linguistic research (Barnes, p. 43). Jeoly may have been buried in an unmarked grave in St Ebbes’ churchyard in Oxford (Angel). Sadly, his story does not end there. Before the burial, his tattooed skin was removed by the Oxford University surgeon Theophilius Poynter and preserved at the School of Anatomy in the Bodleian Quadrangle.

Jeoly was not the first ‘exotic’ slave to have been exhibited in England for pseudo-scientific ‘curiosity’ and he would not be the last either. With regard to Oxford, Pointer’s handwritten account tells of tattooed West-Indian Princes who were displayed in 1719.

Collections of ‘curiosities’ like Pointer’s scrapbooks were already criticised as sensationalist in his own time. Pointer defended them arguing they offered ‘a microcosm of God’s creation [that leads] us to the Great Author of Nature, & not only serve to puzzle the Philosopher, but also to admonish (if not convince) the Atheist’ (Barnes, p. 32). Today, they are rightly regarded as pseudo-scientific at best and unethical at worst.

References

Angel, Gemma, ‘Tattoos that Repel Venomous Creatures! The Tragic Tale of Prince Giolo (27 May 2013)’, University of London: Researchers in Museums Blog (27 May 2013)

Barnes, Geraldine, ‘Curiosity, Wonder, and William Dampier’s Painted Prince’, Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 6 (2006), 31–50

Notes

MS 253 is fully digitised at Digital Bodleian and a catalogue record describing the manuscript is available at Archives Hub.

This text about 'Prince Giolo' was originally written for the St John’s Library exhibition The President, the ‘Prince’ and the Hedgehogs: An Exhibition in honour of Ruth Ogden, Deputy Librarian 1987–2022, on the occasion of her Retirement, Hilary Term 2022.