The Vestments Conference, in Review

Hannah Skoda, Keeper of the Vestments, has reviewed the wonderful experience that was the Vestments Conference for us.

"On 8th and 9th March, we enjoyed a feast of talks, demonstrations and workshops centred around the vestments collection at St John’s. We are now working on a scholarly catalogue about our collection, which will be published with the Boydell Press – so watch this space!

We opened with a talk from Malcolm Vale about the dramatic history of the vestments at St John’s. The first mention of the college collection dates from 1573, and mentions ‘Church stuff’. Malcolm makes the strong case that the vestments were most likely provided by the founder of the college, Sir Thomas White, in 1555–7. There are hair-raising stories about the preservation of the vestments in a Welsh slate mine during World War II, and the rediscovery of a beautiful liturgical banner in an old chest in the President’s attic in the 1990s. The latter narrowly escaped being thrown onto a skip, when Malcolm was called to take a look.

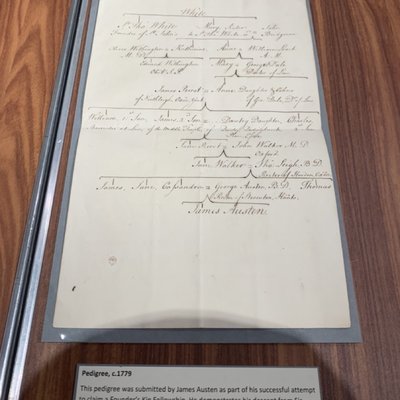

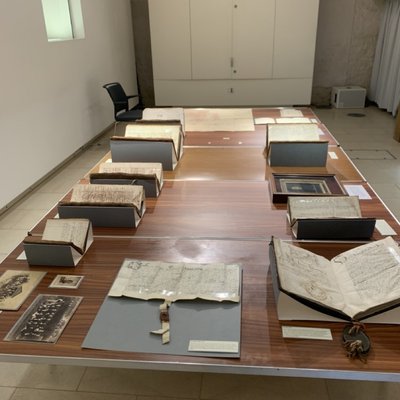

The St John’s archivist, Michael Riordan, then traced what we know of the vestments and their context through the college archives. He told us of the 1602 document by the then president of the college, Ralph Hutchinson, referring to the ‘superstititous Church ornaments’ given by Amy Leech, the founder’s niece. She seems to have been instrumental in saving the vestments from destruction during the Reformation, squirreling them away at Fyfield manor (she was also, incidentally, an ancestor of Jane Austen). The vestments are an intriguing strand in the religious stance of the college over the course of the seventeenth century (and of course its famous association with Archbishop Laud). Michael also curated a wonderful exhibition in the Barn Gallery of documents relating to, and contextualising, the textiles collection.

" There are hair-raising stories about the preservation of the vestments in a Welsh slate mine during World War II, and the rediscovery of a beautiful liturgical banner in an old chest in the President’s attic in the 1990s. " Hannah Skoda

We then took a step back from the collection itself in its college context, to hear about the ways in which such textiles would have been used in the liturgy. Matthew Cheung-Salisbury from University College, Oxford, explained that we are far too ready to think about the liturgy in textual terms: rather, we should think about it being sung or intoned, and approach the vestments as material witnesses of these rites. The vestments were there to be seen, to be worn, and to be manipulated: and, as he explained, these processes helped to transform the priest as person into celebrant of the mass. We heard about the Sarum rite, used across the south of England. A document in Corpus Christi college (MS 44) gives details on how the vestments were to be used in colleges, which colours were to be worn at which times in the Church calendar and so on. We heard about the experience of a priest in wearing these vestments: the sheer heaviness of wearing a cope, how this makes one occupy space differently, the ways in which the putting on and taking off marked points in the liturgy – the priest would remove the black cloak at the moment of the Easter service which marked the passing from death to life. A major source is Guillaume Durand’s detailed explanation of how vestments should be used, dating from 1286, and very influential right up until the second Vatican council of the twentieth century. Durand listed the symbolic meanings of different aspects of the vestments: the hood indicated supernatural joy, the length demonstrated the perseverance to the end by Jesus, the opening at the front indicated the openness of a life of holiness, the fringe represented the tribulations of the world, and so on. The sheer beauty of these textiles really mattered: this was the moment when the priest became not just a man, but a priest – worshippers were to be in the presence of divine beauty.

Katherine Wilson from the University of Chester then gave us a wonderfully rich sense of the sophisticated trading networks and commercial relationships which underpinned the production of these textiles. These objects were part of trading networks which stretched across Europe, and which drew on materials from across the globe: the Persian Gulf, Sri Lanka, India. We heard about the mercers and merchants financing this work, and the aristocrats who so often commissioned it and failed to pay: the commercial risks for merchants were high. A comparison with paintings is instructive: the outlay for textiles on the part of the makers is much higher, as the materials are so costly. It is rare that any individuals can be identified, but the Setter family, for instance, seem to have been producing vestments for 40 years, an extraordinary testament to the continuity of a family tradition in a particular trade and craft. Katherine explained the innovations which took place in the fifteenth century, as pre-made patterns were increasingly used to speed up the process. There’s an interesting gendered dimension, as women seem to have been centrally involved in this kind of production and commerce.

Kate Heard from the Royal Collection Trust provided a richly detailed account of the embroiderers themselves. We heard that it is impossible to tie a particular embroiderer to a particular textile, but nonetheless there is rich detail on what became a London-based craft, and one which was emphatically a sellers-market. Kate again discussed the relationship between this trade and that of painters, the role of templates and patterns and the kinds of artistic variation and innovation which this in fact fostered. Clearly a wide range of patrons were interested in purchasing this material: rather movingly, we heard how parish churches might buy vestments piece-meal as they could afford them, assembling them over time.

The international scope of this trade was further developed by Richard de Beer from the Catharijneconvent museum in Utrecht. He showed the fabulously wide array of vestments surviving in this wonderful collection, and detailed the very different methods used by nineteenth-century collectors which have both assured the survival of these pieces, and in some cases, damaged them quite dramatically. But adaptation and re-use is part of the story of many of these textiles, and it was fascinating to hear about how, for example, fifteenth-century copes might be made into chasubles in the seventeenth century: the so-called ‘Spiritual Virgins’ of Haarlem in the seventeenth century seem to have had a particular interest in English vestments.

The story of recovery and re-use was expanded by James Clark of the University of Exeter. He began by telling of the process of finding new homes and new purposes for late medieval vestments at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The story of the St John’s vestments is so bound up in what we think we know about the Reformation, so it was fascinating to hear that there was no single watershed of destruction or dispersal of medieval vestments, but rather a piecemeal process and a lot of reuse. We were also encouraged not to see everything in confessional terms. James outlined the gigantic scale of the vestments which were made available by the dissolution and changes to the liturgy: the journeys of these textiles can be traced through inventories, and reveal a fascinating and nuanced history of reuse, often by clergymen themselves as parish churches benefitted from the windfall of rich garments now available.

Ingela Wahlberg from the University of Uppsala then enabled us to zoom in once again on the vestments themselves in minute detail. As a practitioner and researcher, she provided a mini-history of the development of particular stitches, and a sense of the sheer meticulousness and detail of the finished pieces. Perhaps most fascinatingly, she was able to show how the individual stitches – whilst following a set technique – often reveal particular stylistic or even personality traits on the part of their stitchers.

We then moved away from the vestments for a while. Clare Hunter, author of Embroidering her Truth, a beautiful new history of Mary Queen of Scots, gave us a richly illustrated account of the ways in which embroidery for Mary was a powerful form of self-expression. She showed how Mary’s stitches could be both consolation from the embattled and imprisoned queen, and resistance as she encoded messages into the images.

Helen Wyld, from the National Museums, Scotland, provided a detailed account of the tapestries which hang in the President’s Lodgings at St John’s. We were then lucky enough to visit the tapestries and see the details close to. St John’s owns two mid-sixteenth-century tapestries, as well as an early seventeenth-century panel. These are extremely rich textiles, with lots of metal-wrapped threads. Helen made the powerful case that these tapestries were probably created for private chapels – they are not on the scale of monumental tapestries made for covering the walls of rooms. The third tapestry depicts the scene of the supper at Emmaus, after a painting by Titian displayed at the court of Charles I in 1627: Charles was trying to present himself as a great collector, but this was an interesting choice of image with its eucharistic resonances. The tapestry was produced by the Mortlake workshop. A guidebook to the college in 1868 states that this tapestry used to hang above the Chapel altar.

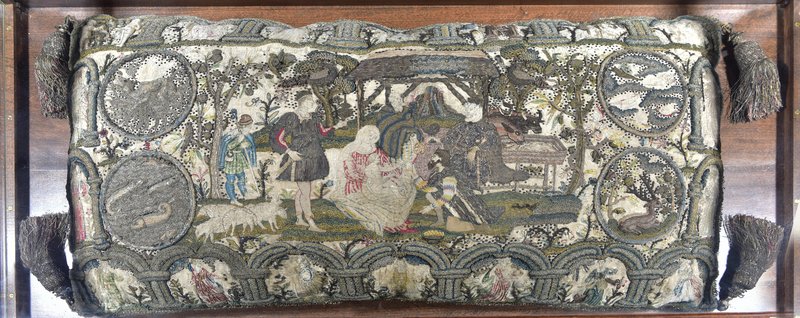

St John’s also owns a rather unusual cushion. Mary Brooks (Durham University) set it in the context of the continued presence of Catholic objects of faith in seventeenth-century England. Much production seems to have moved to a domestic context, and we heard about the house of Isabelle Hampden in Stoke Poges, raided by the puritanical Paul Wentworth in the later sixteenth century: the list of things seized includes a number of embroideries, including several still on their embroidery frames. The St John’s cushion likely comes from the workshop of Edmund Harrison (1590–1667), who was a remarkably flexible man: he was the king’s embroiderer, then made heraldic tabards during the Commonwealth, returning to work for Charles II. Mary wondered whether the object is in fact a cushion, or perhaps yet another example of repurposing.

We then heard about historical reconstruction. Jane Malcolm Davies from the University of Copenhagen outlined the methodological goals and rigour of this process. We learned about the ways in which reconstruction can yield new insights into making and purpose. The talk was richly illustrated, and we all got to try on a Tudor cap. Lesley O’Connell-Edwards, who has been working on a project on ‘Holy Hands’, showed us her own reconstructions of knitted liturgical gloves. These were recognised as part of the episcopal regalia from the second half of the twelfth century. We heard again how Durand allegorised aspects of liturgical gloves: they were to be seamless, symbolising the prelates’ adherence to the Church, and made of goat skins to reflect the story of Rebecca. The examples that were passed round were exquisite.

" Perhaps most fascinatingly, she was able to show how the individual stitches – whilst following a set technique – often reveal particular stylistic or even personality traits on the part of their stitchers. "

Then it was time to see these techniques in action. We were treated to a wonderful demonstration of tapestry techniques by Rudi Richardson from Dovecot Studios. The beauty of these artworks is so striking, and it is just fascinating to see the process as opposed to merely hearing about it. Tanya Bentham, a specialist in opus anglicanum, then demonstrated the main stitching techniques used by medieval embroiderers. Participants also had the chance to participate in workshops trying out these stitches for themselves. It was incredibly fun – and increased my awe of medieval artists and craftspeople still further.

A final treat was a trip to the Bodleian, to see a wonderful array of manuscripts chosen by Andrew Dunning, R.W. Hunt Curator of Medieval Manuscripts at the Bodleian Library. These are things of such astonishing beauty, and Andrew teased out a number of connections with textiles. We saw notational manuscripts, the material of the liturgy alongside the vestments. We saw illuminations which showed vestments being worn. And we saw manuscripts now bound in the cloth of repurposed vestments.

It was a wonderfully informative couple of days, and I would like to thank the College and all the participants for their intellectual generosity, enthusiasm and curiosity. There was such a sense of shared excitement – the College does indeed care for a collection of great historical significance and intense beauty."

As a reminder, the Vestments Gallery is open to the public every Term on Saturday of 7th Week. Come experience this rich collection for yourself!