There and Back Again

On Thursday 2 June 2016, St John’s alumni gathered at the London

Mathematical Society to hear Professor Paul Tod, Official Fellow and

Tutor in Mathematics, lecture on ‘Black Holes in General Relativity’.

On Thursday 2 June 2016, St John’s alumni gathered at the London

Mathematical Society to hear Professor Paul Tod, Official Fellow and

Tutor in Mathematics, lecture on ‘Black Holes in General Relativity’.

Professor Tod opened by explaining the appeal of black holes: an exciting idea that can be described without ‘scary formulas’ or misleading simplification. He began his account in the eighteenth century, with the clergyman and natural philosopher John Michell. Michell’s 1783 paper to the Royal Society on ‘Dark Stars’ had laid the foundation for the search for black holes, but his fundamental premise (that light is slowed by gravity) was incorrect. The search was on for the right way to do Michell’s argument.

With the acceptance that the speed of light is the same for all observers, scientists were able to develop the notion of special relativity and explore how gravity bends the path of light. In 1915, Einstein had predicted that the path of light is not straight, and this was confirmed by Eddington in 1919. But although the curvature of spacetime was described by John Wheeler (‘Spacetime tells matter how to move. Matter tells spacetime how to curve’), in what Professor Tod called ‘the kind of thing you could have in cross-stitch over your bed’, the final piece of the Black Hole puzzle remained elusive. How could we detect something that is tiny, completely black, and millions of miles away?

Professor Tod concluded by examining the exciting new research to come out of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). Just two days after they were turned on for the first time, the measuring instruments developed at LIGO detected ripples in the fabric of spacetime – gravitational waves – that prove the existence of black holes. Professor Tod ended his lecture by speculating about the wealth of further information that these measuring devices would be likely to bring to research on black holes.

Questions from alumni ranged from curiosity about Michell’s original conception of light, through the nature of black holes, to the construction of the LIGO interferometer machines. The discussion ended with a reflection on the funding mechanisms for modern science and how these might affect the way that research is carried out.

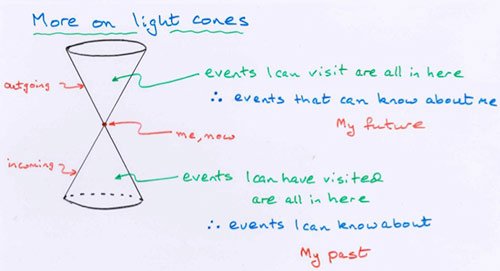

With time increasing up the page, the light cone represents an incoming then outgoing flash of light, expanding like ripples on a pond. Since nothing can travel faster than light, the cone serves to demarcate the future of an event as the events that can be reached from it and the past as the events through which it can have passed.

With time increasing up the page, the light cone represents an incoming then outgoing flash of light, expanding like ripples on a pond. Since nothing can travel faster than light, the cone serves to demarcate the future of an event as the events that can be reached from it and the past as the events through which it can have passed.