Why Reading Matters

The printing press is sometimes cited as one of the world’s greatest ever inventions, and rightly so. Imagine the last 575 years of human history without it, and its two intertwined descendants, the mass production of books and the mass spread of literacy.

Behind the printing press is another remarkable invention – writing itself. Via the cultural invention of writing systems, we can share our thoughts, ideas, knowledge and dreams with those who share our code. The written word transcends time and space and thanks to the printing press and all that’s come since, there is an ever-growing repository of shared knowledge for us to interact with.

As literate adults, we rarely stop to think of the underlying complexities of what we do as we read, or the enormity of the task facing young children. First and foremost, children need to learn the basics of how their writing system works – how, in English for example, the 26 letters work in combination to connect print with meaning. Beyond this, there’s still much for children to learn and do. Pick up most children’s story books and you will find new words, complicated grammar, hazy connections and fantastical – and sometimes outright false – information about the world. How do children make sense of this? Comprehension also depends on the reader appreciating the mental state of characters – what they know, believe and feel, and how this relates to the unfolding plot. Non-fiction brings its own demands with disciplinary specific knowledge often carried by rare and abstract words embedded in complex sentences. Different sources can point to different conclusions, and how do children learn to integrate and build knowledge, and separate fact from fiction? And the child-turned-writer needs to be able to do all this in reverse – to use written language effectively to transport their intended message onto the page and into the minds of the reader.

Becoming literate is an incredible feat, and we now understand a good deal about its neural, cognitive and language foundations. While many scientific questions remain, two pillars remain central to the heart of learning to read: teach children to read directly and explicitly; and provide substantial opportunities for varied and extensive practice via high-quality texts that captivate and inspire as they incrementally equip children with knowledge about how the world works, be it real or imagined.

Had I been writing a few years ago, I might have stopped here, perhaps after noting that being able to read provides a young person with better access to education and learning, success in the workplace, to physical and mental health and well-being, and to culture. If any policymakers were listening, I might have said that teaching children how to read and making sure they have easy access to books is surely one of the most important jobs of the state.

This remains the case, but there is now a need to add more. In the UK, 1 in 4 11-year-olds are not meeting expected targets in reading and writing, and children are choosing to read and write less. Much less. Headline figures are startling, with fewer than 1 in 5 children reading daily and just 1 in 10 writing something each day in their free time; both statistics amount to 20% drops over recent years. The reasons for this (in the context of the UK at least) are nuanced, complex, and systemic. Worryingly, declines in reading and writing are not distributed evenly, but appear to be associated with poverty and they are gendered, with boys engaging less than girls. Library provision is being lost from schools and again, this reduction is not distributed evenly.

It is also easy to ‘blame’ social and digital media and AI. Historically, new technological developments have often raised societal concerns, including the mass production of books and the spread of literacy itself. New tech is changing teaching and learning and the promise of personalised learning apps that reward and incentivise is exciting. But, cognitive offloading may have consequences, and experts warn that many students now lack the capacity to sustain attention and engage with longer texts, heralding a literacy crisis. Perhaps we will return to a society in which high levels of literacy are once again the preserve of a privileged minority.

Not surprisingly, there are calls to action. Next year has been designated the National Year of Reading, led by the government and the National Literacy Trust. The Sunday Times has launched a campaign to Get Britain Reading, with a call for all of us to pledge to read for pleasure for at least 10 minutes a day, and the BookTrust is driving the Reading Rights campaign to make sure every child has access to books and reading from the earliest years.

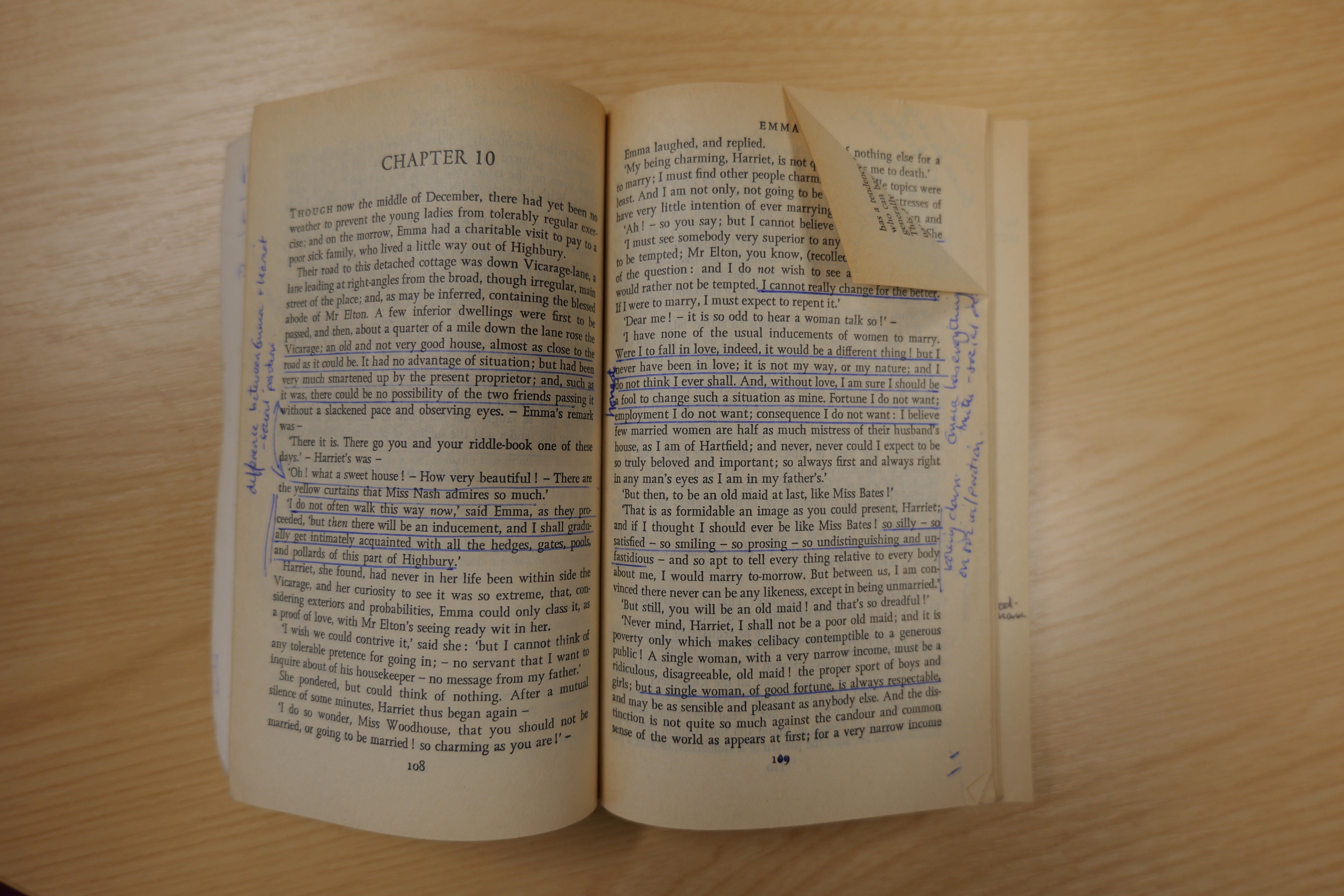

Professor Kate Nation's annotated copy of Emma.

Professor Kate Nation's annotated copy of Emma.

Alongside these national campaigns, there are many questions to ponder and debate via our own year of reading at St John’s, starting with our celebration of Jane Austen. A conversation with ChatGPT tells me that Pride and Prejudice is her most popular novel, closely followed by Persuasion and Sense and Sensibility. For me, without a doubt it’s Emma – and I realise now that this isn’t only for its characters and humour. It was one of my A-Level texts and it is so evocative of time and place. I think about the book and I’m immediately back to my 17-year-old self as much as I’m with Emma and in her world, with Harriet Smith, Mr Elton and Mr Knightley. I pick up the book and it still smells of my old school, all these years later, and reading my scribbled marginalia is raising a smile. This feels like a lesson for the magic of reading.