29. Canterbury Quad, by William Nicholson

William Nicholson (1872-1949), Canterbury Quad, c.1902-1904, oil on canvas, 52.1 x 57.2 cm

William Nicholson (1872-1949), Canterbury Quad, c.1902-1904, oil on canvas, 52.1 x 57.2 cm

This painting of Canterbury

Quadrangle, bathed in golden afternoon

light has something of an afternoon scene in a Venetian piazza about it – the

quiet atmosphere and strolling figures as well as the emphasis upon light and

shadow, which emphasizes the spaces behind the arches as it moves from overcast

shadow to bright sunshine from left to right across the horizontal composition.

In part, this piazza-like effect emerges from the undefined interior space of

the quad. Today, we are used to the delineations of grass and paths, but here

the close palette merges this space into the ochre sandstone of the

architecture. It could be a hazy Venetian setting from Henry James’ novel The Wings of a Dove, if it wasn’t also

so unmistakeably an Oxford quad.

Punctuated by the green of the

garden, glimpsed – as now – through the far gate under the imposing bronze

statue of Henrietta Maria by the French Huguenot sculptor, Hubert Le Sueur, the

viewer is enclosed in the scene, standing in the rich purple of the foreground

shadow that contrives to show the fourth wall of the quad, as if behind us. There are women in

the quad, but all accompanied by men (it is decades before the admission of

women to St John’s), which suggests that they are visitors, perhaps the wives

of current fellows or visitors to the college: we might conjecture that

this is a weekend or vacation afternoon, or even the afternoon of a garden

party or event.

William Nicholson himself fits

this Edwardian atmosphere. Described

by the National Portrait Gallery as ‘a

distinguished and dandified Edwardian portrait painter, poster designer and

painter of still lifes’, he was known for his immaculate attire, appearing to

paint dressed in his customary white trousers and high collar (even when

painting on the Sussex or Wiltshire downs) and clutching a folding chair.

Nicholson was also a book

designer and illustrator, and the strong, simplified black lines of his

lithographs for an alphabet book are perhaps the best known of all his works.

But he was also a wide-ranging painter, and his still-lives have a concentrated

focus upon the interrelation between objects that clearly influenced the highly

abstract work of one of sons, the modernist painter Ben Nicholson (1894-1982).

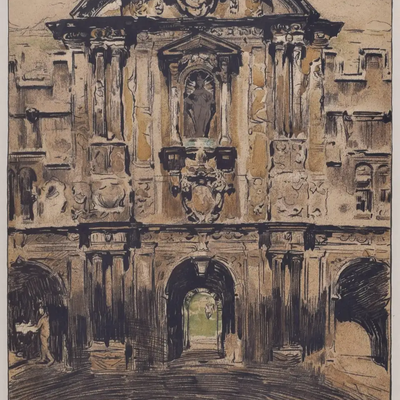

Between 1902-1904, whilst

Nicholson was living in Woodstock, he made a series of studies of Oxford,

including numerous images of the colleges. These became a series of

watercolour, chalk and pen drawings, published in 1905 by the Stafford Gallery

as two portfolios of lithographs, with descriptions by Arthur Waugh – the

father of the novelist Evelyn Waugh. Amongst these is a study of the Canterbury

Quad (see below), which informs the painting. However, in comparison to the

hazy, still scene of the painting, Nicholson’s use of line has a dynamism that lies

somewhere between the gothic drawings of the eighteenth-century Swiss painter

and draughtsman Henry Fuseli and the twentieth-century artist, John Piper

(discussed in an

earlier blog). Like both these artists, Nicholson’s line is descriptive,

animating the architectural detail of the quad such that it becomes as engaging

a subject as the actual living figure moving beneath the arches.

The cross-hatching and use of a

thick black wash turn again to the way in which light and shadow interplay

across the ornate surface of the buildings. In this lithograph there is drama

and also brevity, caused by the sense that lines have been applied with some speed

– as if following the forms of the coats of arms and the capitols as fast as

the eye traces them, securing them in this drama of sunlight and shade before

it passes. This is typical of Nicholson’s illustrative style, and it is

compelling – enchanting even. In the occasional daub of paint (such as the

flecks of white that indicate light reflected on the glass window panes) and in

the loosely painted purple shadow that dominates the foreground, there are

vestiges of this in the painting. Like Nicholson’s 1903 painting, Morris Dancers at Blenheim Gate (see

below), there is a pastoral element – the golden light and atemporality of the

morris dance evoking a crepuscular, nostalgic vision. The brushwork and the

close tonalities of these paintings also speak to the influence of the painter

James Whistler (1834-1903), who encouraged Nicholson to concentrate further

upon oil painting.

At a moment when we might begin

to hope that there is an end in sight to the pandemic, maybe we can look

forward to a summer with some echoes of Nicholson’s balmy afternoon scene in

Canterbury Quad.

Dr Jennifer Johnson, Junior Research Fellow in History of Art

Dr Jennifer Johnson, Junior Research Fellow in History of Art