22. Stone Drawing, by Susanna Heron

Exterior detail: Stone Drawing, 12 December 2017, 12.14pm. Photograph & Artist copyright Susanna Heron © 2020

Exterior detail: Stone Drawing, 12 December 2017, 12.14pm. Photograph & Artist copyright Susanna Heron © 2020

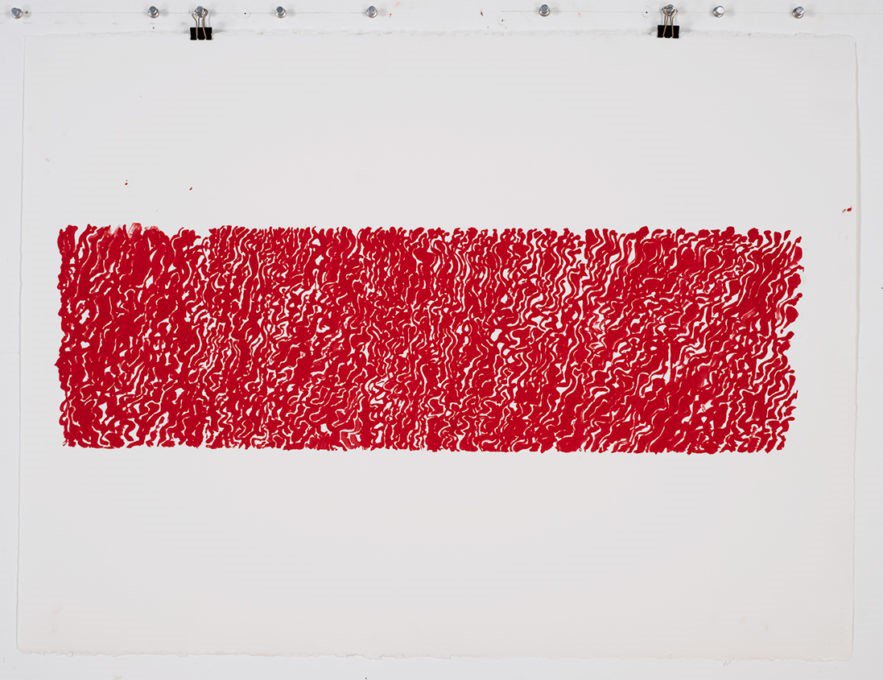

Susanna Heron, Red Drawing (St John’s) 02, 2015. Cartoon for Stone Drawing. Oil on paper. 57 x 76 cm. Photograph & Artist copyright Susanna Heron © 2020

Susanna Heron, Red Drawing (St John’s) 02, 2015. Cartoon for Stone Drawing. Oil on paper. 57 x 76 cm. Photograph & Artist copyright Susanna Heron © 2020

Susanna Heron’s Stone Drawing (2014-2019) defines the

atmosphere of the new library and study centre at St John’s. A negative relief

carving on both the exterior and interior limestone walls, the effect on the

passer-by or inhabitant of the space (viewer is not quite the right description

here) is akin to that of an ancient processual chamber or the carved sandstone

relief of the Shrine of Taharqa (c.680 BC) which can be found in the ground

floor galleries of the Ashmolean Museum.

The walls of the shrine, once brightly painted, now evidence the toll of wind

and sand, as the visibility of the figures and hieroglyphs wanes and falters in

patches. Heron’s Stone Drawing,

despite its newness, is equally unafraid of weather and time. In her notes

about the piece, quoted in the book accompanying the opening of Stone Drawing in 2019, Heron writes:

‘During its long gestation, and now that it is complete it remains in my

imagination – how it will be in the future, how it will weather and soften and

stain on the exterior, how it was in sunlight at midday on a certain date.’[1]

Reached via Front Quad and Canterbury Quad through a panoply of carved surfaces

aging at different rates and in different ways, this impermanent quality sits

authoritatively within such a permanent structure – exacerbated perhaps in the

view from the gardens, whose seasonal fluctuations impel this instability.

The tectonic qualities of Stone Drawing drive its horizontal

emphasis; it is rhizomatic in the way that form reaches across the surface in

an almost-formation of figures that slip, as if at the last moment of viewing,

into a flowing abstract whose pattern reverberates in refusing repetition or

sequence. A project such as this has many stages, the lines of the original

drawing, Heron writes, ‘form a sort of thicket, appearing as a jumble of lines

both falling across the grid of the wall and taking account of it, governed by

an accumulative, natural law.’[2]

These original drawings are made with relief in mind: lines are also edges and

divisions, they indicate what will become shallow depths that nevertheless

create shadows across the surface. These shallow depths, grids, and shapes

recall the abstract work of Ben Nicholson (see, for example, 1935 (white relief), 1935). A

central figure in the International Modernism movement in Britain, Nicholson

was interested in an abstraction that synthesized architectural and design form

with painterly and sculptural aesthetics. In his reliefs, multiple shapes and

small shadows enable the play of various forms within the same physical plane –

but without the organic formal qualities we also experience in Heron’s work.

Where Nicholson’s is fixed, in part related to his utopian vision of social

harmony, Heron’s forms flow within the stone towards a different kind of

harmony.

Whilst it is also tempting to

relate the way Heron thinks about working with stone through the curves and

patterns of Stone Drawing to the

tradition of direct carving in British sculpture – most famously practiced by

Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore – actually the planning and importance of

specification drawings in Heron’s process take the work away from the creative

hand of the craftsman. This is not to close down its meaningful possibilities

in any way, but rather to liberate the work itself from the figure of the

craftsman, from the expectation of self-expression, and to open art to a new

potentiality. ‘You can see the vector file as

the work, it is like DNA, proof of the fact’, Heron told me: ‘Once it is

carved in stone, light is activated and things start to happen’ – this activity

is enhanced by the placement of the piece too, its instantiation in a physical

environment is its beginning in many ways.

The title also causes us to

reflect on forms of expression and their relationship to medium: drawing in one

sense is a very basic form of expression but also often associated with refined

line and precise rendering. These qualities are present in Stone Drawing, and yet the act of drawing here also has an

immaterial form – the original drawing is recreated by the artist as the vector

file that the machine will use as the cutting line: it is drawing as

potentiality, awaiting the medium to re-embody it. The cutting and the

qualities of the stone itself become part of the new materiality of the drawing.

The erosions that will act upon the surface over time will also write their way

into the work, as does the shifting pattern of shadows which enacts a kind of

gestural drawing on a daily basis.

It is a work that draws and redraws itself both

as light and time play out upon the surface and as we move in the space it

inhabits. Let’s hope in 2021 this is a space we can all visit more often and

more freely.

Copies of the book produced for the opening of Stone Drawing are available here.

More information about the artwork is available on the St John's website and on Susanna Heron's website.

Susanna Heron also discusses the artwork in this YouTube video, produced by the Art360 Foundation.

View the artwork on Art UK here.

[1] Susanna Heron, unpublished notes, 2019, quoted in Caroline Collier, ‘How things are and how things are not: encountering Susanna Heron’s Stone Drawing at St John’s College, Oxford’ in Stone Drawing, St John’s College Oxford: Susanna Heron (London: Abson, 2019), p.26.

[2] Susanna Heron, ‘Notes on Stone Drawing’, ibid. p.34

Dr Jennifer Johnson, Junior Research Fellow in History of Art