Jane Austen: Juvenilia

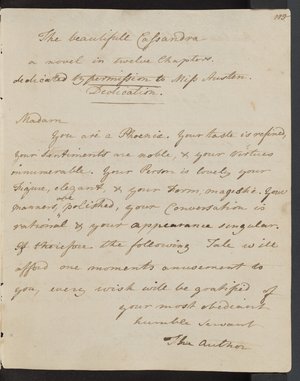

‘The Beautifull Cassandra: A Novel in Twelve Chapters’, was written by Jane Austen in 1788, when she was just twelve years old. It is one of the most absurd and irreverent of her early, unpublished works.

In a mere 367 words, or four handwritten manuscript pages, it recounts the heroine’s misadventures on the streets of London as she sets out ‘to make her Fortune’. Its surprising brevity, despite its grand title, and the unbecoming, almost manic, behaviour of its female protagonist, satirises both the form of the eighteenth-century novel and the conventions of female decorum that the genre customarily assumes.

Jane Austen dedicated ‘The Beautiful Cassandra’ to her elder sister of the same name, praising her ‘polished’ manner, ‘refined’ taste, and lauding her other ‘innumerable’ virtues. However, although the novel’s heroine shares Cassandra Austen’s name and age (sixteen), it becomes clear that she possesses very few of Miss Austen’s virtues.

In the novel’s opening two chapters, Cassandra steals a bespoke bonnet that her mother (a milliner, or hat-maker) has just finished for an unnamed Countess, ‘place[s] it on her gentle Head & walk[s] from her Mother’s shop to make her Fortune’. In late Georgian London, it would have been considered unimaginably indecorous for a young, unmarried woman to be walking the city streets alone – particularly so in Mayfair (where Cassandra’s mother’s shop is situated), which was dominated by sociable young men. These rules and expectations, we may imagine, would have been firmly impressed upon Jane and Cassandra Austen when they visited London earlier in 1788, and it is likely the strict social norms relayed to Jane and her sister during this visit inspired the misadventures of her heroine.

Walking alone down Bond Street, Cassandra encounters a handsome young viscount, peacocking on the street corner. Surprisingly, however, she denies him any opportunity for badinage or flirtatious banter, offering a curtsey before walking briskly on. Contrary to the expectations of readers of contemporary novels – who might anticipate the viscount to emerge either as a potential love interest or as a threat to her virtue – Cassandra ignores and escapes male attention entirely.

From here, Cassandra ‘proceed[s] to a Pastry-cooks’, where she ‘devour[s]’ six ice-creams, refuses to pay for them, and then attacks the cook, ‘knock[ing]’ him down before once again calmly ‘walk[ing] away’. It’s striking that she doesn’t just ‘eat’ or ‘enjoy’ these ice-creams, but ‘devours’ them: her desire for the frozen treats is voracious and entirely unchecked, either by good manners, social expectation, or such small practical matters as money.

Cassandra continues to thumb her nose at notions of female decorum by riding a Hackney Coach alone, travelling four miles to Hampstead and immediately back again, before refusing the driver his pay. When the driver demands payment for the wasted journey, Cassandra places her stolen bonnet on his head and runs away. Although a bespoke bonnet would more than compensate for the cost of the journey (setting aside the fact that it is stolen property), the gesture is symbolic: by leaving the driver wearing a woman’s hat, Cassandra both mocks and emasculates him.

Boldly walking bald-headed through Bloomsbury Square, Cassandra bumps into a mysterious acquaintance, and her characteristic composure is momentarily shaken. Upon meeting Maria, she trembles, blushes, and is startled into silence. Her sudden speechlessness prevents any explanation for her unusual reaction. Why, we are left to wonder, is this woman also wandering the streets alone, and how does she know our heroine? However, the ‘mutual silence’ that exists between the two women is telling, and there’s a certain shared solidarity in their encounter. The enigmatic meeting hints, perhaps, at a community of adventuresses roaming the city unaccompanied – though there is still, on occasion, cause for embarrassment when their independent paths cross.

After an absence of ‘nearly 7 hours’, Cassandra returns home to Bond Street, where she is pressed to her mother’s bosom. Smiling and whispering to herself, Cassandra reflects that ‘“This [was] a day well spent”’. The word ‘spent’ is certainly apt: although Cassandra set out to ‘make her Fortune’, her day's pleasure comes from taking, consuming and stealing, not ‘making’ anything at all! Yet despite her transgressions, she is welcomed home warmly by her parents and appears to suffer no ill consequences for her behaviour.

In a period in which young English women were expected to be like Cassandra Austen – with ‘polished’ manners, ‘refined’ tastes, and abundant other virtues – Jane Austen’s novel, and the adventures of its heroine, might be considered a fantasy of unchecked pleasures, with the prospect of punishment suspended.

A modern edition of the ‘Beautifull Cassandra’ can be read online here. Jane Austen’s original notebook, containing her earliest surviving juvenile works, is now held by the Bodleian Library (MS. Don. E. 7) and has been digitised here. ‘The Beautiful Cassandra’ can be found at pp. 115–19.

In January 1793, aged seventeen, Jane Austen became an aunt for the first time. To celebrate the birth of her niece, Fanny Catherine Austen, Jane wrote a series of short pieces that form a kind of girls’ guide to behaving badly. This mischievous series explicitly satirises the restrictive limits placed on female education and behaviour in contemporary conduct manuals.

‘A Letter from a Young Lady’ — which matter-of-factly recounts a young woman’s successful career as a murderer, blasphemer and perjurer – is the most outrageous and the funniest of the pieces Austen dedicated to her infant niece.

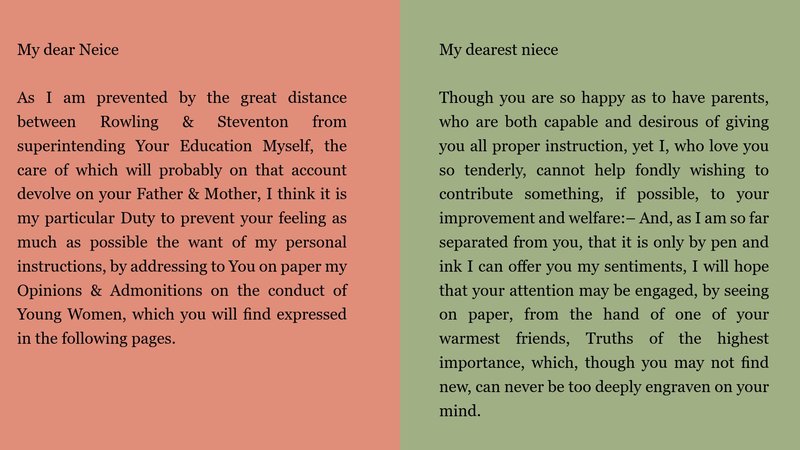

The object of Jane’s satire in ‘A Letter from a Young Lady’ is obvious when one compares her dedication to her niece, Fanny (below, left), to the first letter in Hester Chapone’s hugely popular conduct manual, Letters on the Improvement of the Mind, Addressed to a Young Lady (below, right), first published in 1774. Like Austen’s letter, Chapone’s book was framed as advice from an aunt to her young niece.

However, while works such as Chapone’s offered pious and educational instruction, designed to turn young women into respectable ladies, Austen’s ‘Letter’ gleefully upsets the formula, demonstrating that female vice, not virtue, is rewarded.

Austen’s letter-writer, Anna Parker, begins her letter to her friend Ellinor by cheerfully recounting how she murdered her father ‘at a very early period of [her] Life’ and has since murdered her mother. The shock of this opening is closely followed by Anna’s admission that she has ‘changed [her] religion so often’ that she has ‘not an idea of any left’. Moreover, she confesses to having committed perjury ‘in every public trial for the last twelve Years’.

‘In short’, Anna admits, ‘there is scarcely a crime that [she has] not committed’. She is thus what Chapone would have called ‘a child of destruction’: a wicked girl who deserves eternal punishment and misery. Yet in Austen’s ‘Letter’, Anna’s flagrant immorality is rewarded. She wins the attention of Colonel Martin, an officer in the Horse Guards: an elite cavalry regiment charged with protecting the royal household.

Recounting their ‘singular’ (or peculiar) courtship, Anna informs her addressee that Colonel Martin is the son of an ‘immensely rich’ gentleman. On his father’s death, Colonel Martin was left only a ‘Small pittance’ of around ‘one hundred thousand pound[s]’, with his elder brother receiving the ‘bulk of his [the] fortune, about eight Million’. It is worth noting the absurdity of these sums: with £100,000, Colonel Martin would be at least as rich as the prosperous Mr Bingley of Pride and Prejudice (1813), while his brother’s supposed £8 million would make him the richest man in eighteenth-century England.

Jealous of this immense fortune, Colonel Martin cunningly forged a revised version of his father’s will, naming himself heir. By chance, we are told, Anna ‘happened to be passing the door of the Court’ at which this forged will was presented and helpfully swore to its validity. Whether her appearance at court truly was happenstance, or whether Anna cunningly engineered her opportunity for advancement is left to the reader to imagine… We are told, however, that the perjured couple were affianced the very next day and are to be married post-haste!

This is not a case, then, of feminine virtue being rewarded with marriage, as readers of eighteenth-century conduct manuals and contemporary sentimental romances could come to expect. Rather, Austen’s ‘Letter’ delights in the revelation that vice and impropriety are tools for female social advancement.

Interestingly, where her prospective fiancé stops at disinheriting his brother, Anna goes one step further and concludes her letter by resolving to murder her sister: not for any material gain, but simply for the pleasure of doing so. Austen’s conclusion thus anticipates Rudyard Kipling’s aphorism that ‘the female of the species is more deadly than the male’.

A modern edition of 'A Letter from a Young Lady’ can be read online here.

‘Lesley Castle’ (c. 1792) is an epistolary novel that traces the melodramatic and rambunctious social lives of two families in Scotland and Sussex. The novel’s principal correspondents are two school friends, Misses Margaret (‘Peggy’) Lesley and Charlotte Lutterell. Although the novel abounds in comic sub-plots, its ten letters largely focus on the second marriage of Sir George Lesley, Peggy’s father, and the death of Charlotte’s sister’s fiancé.

The three letters written by Charlotte Lutterell are unmistakably the highlight of the novel and, as several feminist Austen scholars have pointed out, the sections in which the teenage author was having the most fun. Charlotte is a pragmatic and independent-minded woman, who also happens to be utterly obsessed with food.

Charlotte Lutterell’s culinary mania is evident from the outset. Upon hearing that her sister Eloise’s fiancé has been thrown fatally from his horse, Charlotte’s first concern is the fate of the vast amounts of food she has already prepared for the wedding. ‘“Good God!”’ she cries when Eloise gives her the awful news, ‘what in the name of Heaven will become of all the Victuals!’ Charlotte immediately begins issuing military instructions about who should eat what and when in order to minimise waste. Her ‘vexation’ arises not simply on account of her wasted labour – having possibly ‘Roast[ed], Broil[ed] and Stew[ed] both the Meat and [Her]self to no purpose’ – but also from a genuine passion for good food and a desire that dishes she has painstakingly ‘dressed’ be enjoyed by friends and family.

Charlotte’s preoccupation with food even shapes her figurative language. Writing to Margaret Lesley, she describes how her sister was ‘White as a Whipt syllabub’. Charlotte later describes herself as remaining ‘as cool as a Cream-cheese’ while contemplating the enormous task of eating her way through the pantry. Similes in Jane Austen’s work are extremely rare, making these culinary examples all the more striking.

Charlotte attempts to assuage her sister’s grief by referring to her fiancé’s fate as a ‘trifle’, making light of the situation ‘in order to comfort her’. While this initially reads as entirely inappropriate and insensitive, we must remember that, for Charlotte, food – literal and metaphorical – is a mode of care. She is just as surprised when her sister refuses to be comforted by the ‘trifle’ gag as she is by Eloise turning down a cold chicken wing. It remains utterly inconceivable to Charlotte, that anyone might lose their appetite. Meanwhile, her own appetite is entirely undiminished by the day’s tragedy. She sends almost instantly for ‘cold Ham and Fowls’ and begins what she calls a ‘Devouring Plan on them with great Alacrity’. Her mission, as she sees it, is to out-consume grief until the pantry is bare.

In her second letter to Margaret Lesley, Charlotte Lutterell recounts her family’s visit to Bristol for Eloise’s convalescence. While Eloise remains ‘very indifferent’ to food, and worryingly declines in both ‘Health and Spirits’, Charlotte recruits a team of servants to help her eat through the vast quantities of pies, cold meats, and jellies that she brings to Bristol with her. She also complains that the timing of ‘Eloisa’s indisposition’ has brought the family to Bristol at ‘so unfashionable a season of the year’ that there are few ‘genteel’ families with whom she might socialise. As such, she has a poor evening dining out where ‘the Veal was terribly underdone, and the Curry had no seasoning’. Charlotte cannot help but wish that she had prepared the dishes herself.

In her third and final letter to Margaret Lesley, Charlotte reflects on the fundamental differences between her and her sister, Eloise, who remains unable to stomach even so much as a cold pigeon pie. Charlotte admits that no two sisters ever had ‘two more different Dispositions in the World’. Whilst her sister grew up drawing, singing, and performing, Charlotte was consumed by recipes, cooking, and eating. Eloise has fixed her sights on marriage; Charlotte confesses that matrimony has never interested her. Her greatest ambition is to sample the sliced cold roast beef at Vauxhall.

The comedic contrast between the Lutterell sisters exposes a pervasive cultural fiction: that women who eat heartily must be unfeeling, and that women who feel deeply must not eat at all. In ‘Lesley Castle’, Jane highlights the equal absurdity of both assumptions. Charlotte’s appetite and culinary monomania does not preclude genuine affection and concern for her sister, and Eloise’s refusal to eat is shown to be neither virtuous nor sensible but merely debilitating. Through Charlotte Lutterell, Austen sends up the sentimental tradition that equated feminine delicacy with dwindling appetite.

Reading Jane Austen’s letters, we may suspect that the teenage author of ‘Lesley Castle’ was far closer to Charlotte than Eloise Lutterell, or, indeed, any of the heroines of her mature novels who are notably indifferent to food. Austen wrote unselfconsciously about meals she enjoyed and favourite dishes. Writing to her sister, Cassandra, in 1796, Jane Austen wrote with great pleasure about ‘devouring some cold souse’: pickled pigs’ feet and ears. In another later example, Austen notes the care she takes in providing ‘such things as please my own appetite’, observing that a hostess’s own enjoyment is the ‘chief merit in housekeeping’. These candid admissions are distinctly Charlotte-Lutterell-esque and worlds away from the indifferent appetites of her later heroines.

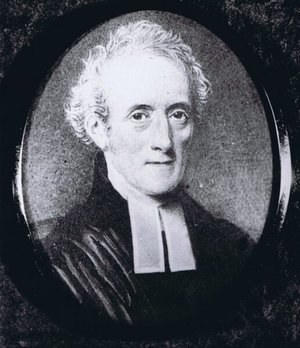

The dedicatee of ‘Lesley Castle’, Henry Austen, would have recognised his younger sister’s resemblance to Charlotte Lutterell. Henry was Jane’s favourite brother, and their close relationship is well illustrated by the playful exchange of notes that precedes the story. In response to Jane’s dedicatory note, Henry composed a comic reply purporting to instruct his bankers, ‘Messrs Demand and Co.’, to pay her one hundred guineas (£105) for her novel. It is very likely that the story was dedicated to Henry to commemorate his graduation from St John’s in the Spring of 1792.

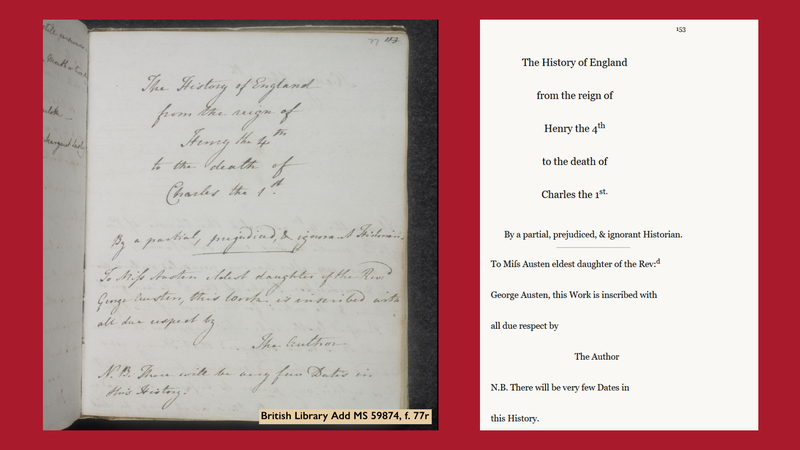

Three weeks shy of her sixteenth birthday, in November 1791, Jane Austen wrote ‘The History of England from the reign of Henry the 4th to the death of Charles the 1st.’ Condensing four centuries of English history into a mere thirty-four manuscript pages, Austen’s ‘History’ offers a satirical characterisation of thirteen monarchs. Austen’s account of each monarch is accompanied by a medallion caricature of the king or queen drawn by her eldest sister, Cassandra, to whom the work is dedicated. Anticipating Horrible Histories by two centuries, Austen’s illustrated ‘History’ is a comedic satire of English monarchs and the genre of history-writing itself.

As the title page to Austen’s ‘History’ declares, this chronicle makes no attempt at impartiality, nor, indeed, it later emerges, is its author much interested in corroborating her opinions with facts. Readers searching for details of persons and events ‘had better read some other History’, Austen warns her reader, admitting that ‘the recital of any Events (except what I make myself) is uninteresting to me’. Rather, this history is described as an opportunity for the author to express her ‘Hatred to all those people whose parties and principles do not suit with [her own]’.

By adopting such an unashamedly partisan style for her ‘History’, Austen was mocking contemporary historians and their self-proclaimed objectivity. Her main target was Oliver Goldsmith, author of the popular school-room History of England from the Earliest Times to the Death of George II (1771), a copy of which was well read and heavily annotated by the Austen family.

In his preface, Goldsmith made exaggerated claims of his own impartiality, yet his narrative quickly betrays evident political and religious biases – an irony that the teenage Austen clearly recognised, wryly noting in the margin of the family copy, ‘Oh! Dr. Goldsmith Thou art as partial an Historian as myself’.

The Austens’ heavily annotated copy of Goldsmith’s History contains several such comments, especially in the chapters relating to the Stuart dynasty (1603–1714). In one marginal note, Jane described the Stuarts as ‘always illused, Betrayed or Neglected Whose Virtues are seldom allowed while their Errors are never forgotten’. The Austens’ pro-Stuart leanings are hardly surprising; Jane’s maternal ancestors, the Leighs, had sheltered Charles I at their estate during the English Civil War and her mother’s cousins were also engaged in writing pro-Stuart works.

Austen’s spirited marginalia in Goldsmith’s History is now widely regarded as a kind of ‘defensive prewriting’, anticipating her full-blooded defense of the Stuarts in her own satirical history. Indeed, championing the Stuart cause and vindicating Mary Queen of Scots (mother of England’s first Stuart king) may well be considered the primary objectives of the 1791 text.

Early in her ‘History’, Austen declares Mary Queen of Scots to be ‘one of the first Characters in the World’ and, from this point forward, every monarchs and political figure is judged on their relationship – tenuous or otherwise – to Mary. Despite being described as ‘as great a Villain as ever lived’, Henry VII earns faint praise for marrying his daughter, Margaret, to James IV of Scotland and establishing the conditions by which a Stuart monarch could inherit the English throne. English Protestants deserved their persecution at the hands of Mary I, Austen adds, ‘for having allowed her to succeed her Brother [Edward VI]’ in spite of the ‘superior Pretensions, Merit and Beauty’ of the Queen of Scots. Austen even goes as far as to suggest that Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, should have been ‘proud’ to be beheaded in 1552, since the Queen of Scots would later share his fate.

However, Austen’s sharpest barbs are saved for Elizabeth I, whom she roundly denounces as ‘the destroyer of all comfort, the deceitful Betrayer of trust’, a ‘disgrace to humanity’ and ‘pest to society’. Austen rails against Elizabeth’s cruelty toward her cousin, lamenting the indignities of the Queen of Scots’ long imprisonment and ultimate execution in 1587:

‘Abused, reproached and vilified by all, what must not her most noble Mind have suffered when informed that Elizabeth had given orders for her Death! Yet she bore it with a most unshaken fortitude; firm in her Mind; Constant in her Religion; and prepared herself to meet the cruel fate to which she was doomed, with a magnanimity that could alone proceed from conscious Innocence’.

Having vociferously defended Mary’s innocence, Austen affords very little space to the other events of Elizabeth’s reign, save only to mention Sir Francis Drake’s circumnavigation of the globe in 1577. In fact, Drake’s adventures are only mentioned as an inside joke; Austen writes that although Drake was ‘justly celebrated as a Sailor’, she ‘cannot help foreseeing that he will be equalled… by one who tho’ now but young, already promises to answer all the ardent and sanguine expectations of his Relations and Friends’. This young sailor was almost certainly her seventeen-year old brother Francis, who had just transferred from HMS Perseverance to HMS Minerva three weeks before Jane began writing her History. The joke is an important reminder that Austen’s juvenilia was written first and foremost to entertain its small coterie of readers: that is, her immediate family.

After Elizabeth I’s death, Austen’s ‘History’ loses momentum. She concedes that the events of the English Civil War were ‘too numerous for [her] pen’ and admits that she was not especially interested by the ‘disturbances, Distresses, and Civil Wars in which England for many years was embroiled’. Her purpose was to merely ‘prove the innocence of the Queen of Scotland … and to abuse Elizabeth’. Having satisfied both ambitions, Austen declares herself ‘certain of satisfying every sensible and well disposed person’ of the innocence of the remainder of the Stuart dynasty. To be a Stuart, or a Stuart-sympathiser, Austen concludes, is argument enough of one’s decency.