Did You Know...?

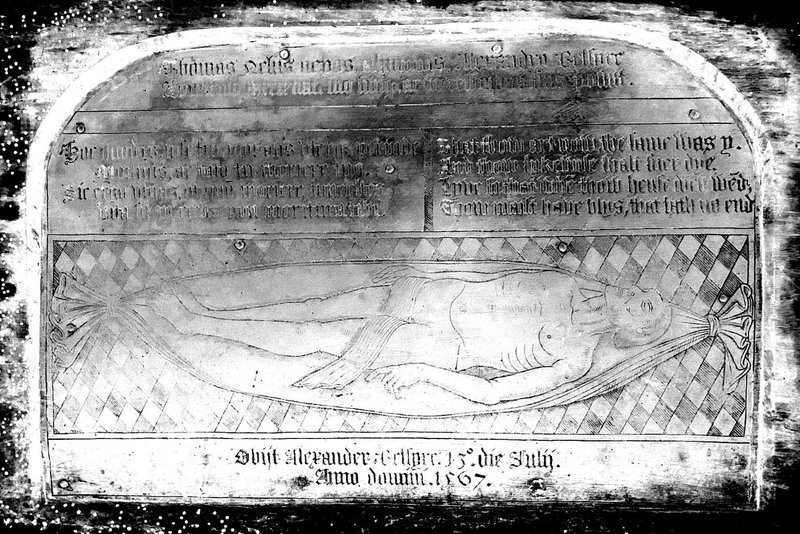

Did you know that the College's first president, Alexander Belsyre (d. 1567), was deprived of the office for theft and perjury?

Belsyre was appointed President in Sir Thomas White's Foundation Charter of 29 May 1555.* However, he was removed from his post by the Founder only four years later. Sir Thomas gave details of Belsyre's dismissal in a letter to the College dated December 1566.†

As recorded in this letter, Sir Thomas reportedly loaned Belsyre £60 ‘in custody for the Colleges use’. Belsyre later maintained that he only owed £40, offering to swear as much before the Senior Fellows of the College and the Vicar of Fyfield. However, Sir Thomas had kept a record of the original payment and was able to use this document as evidence of Belsyre’s dishonesty. The President was swiftly ‘removyd and dysplacyd’ from his office and the Fellows were charge to never ‘admytt, receve’ or suffer Belsyre to ‘enjoye any office, rome, annuytye, or Feloshipp’ in the College.

Belsyre retired to Hanborough in West Oxfordshire. He was later ordered to remain in the town and not to venture beyond two miles of its boundary, being described as ‘an old wealthy and stubborn recusant’ in 1562.††

(Alexander Belsyre's tomb, St Peter And St Pauls Church, Hanborough, Church Hanborough, West Oxfordshire)

References and Further Reading:

* W.H. Stevenson and H.E. Salter, The Early History of St. John's College Oxford (Oxford, 1939), Appendix XIX.

† Early History of St. John's College, Appendix XXIV.

†† Early History of St. John's College, p. 124.

Did you know that William Shakespeare’s grandson, Richard Quiney, was a student at St John’s?

Richard (b. 1618) was the youngest son of Judith Shakespeare, the bard’s daughter, and Thomas Quiney, a vinter (winemaker) from Stratford-upon-Avon.

The Shakespeare and Quiney families had a longstanding connection. Richard’s grandfather, his namesake, was the author of the only surviving letter addressed to Shakespeare, written c. 1598. Even earlier, Richard’s great-grandfather had worked closely with Shakespeare’s father, John, as bailiff and chief alderman of Stratford-upon-Avon.

During his time at St John’s, Quiney benefitted from the patronage of the College’s President, Richard Baylie, to whom he was related on his father’s side. It is likely that President Baylie secured Quiney the post of St John’s Sexton in 1634.

Unfortunately, Quiney died only a few months after he took his BA in October 1638, likely due to bubonic plague. Quiney’s two siblings and his cousin, Elizabeth Hall, also died without heirs, meaning that there are no direct descendants of William Shakespeare’s line today.

Further Reading

J. Pitcher, 'Shakespeare and St John's?', TW Magazine (2016)

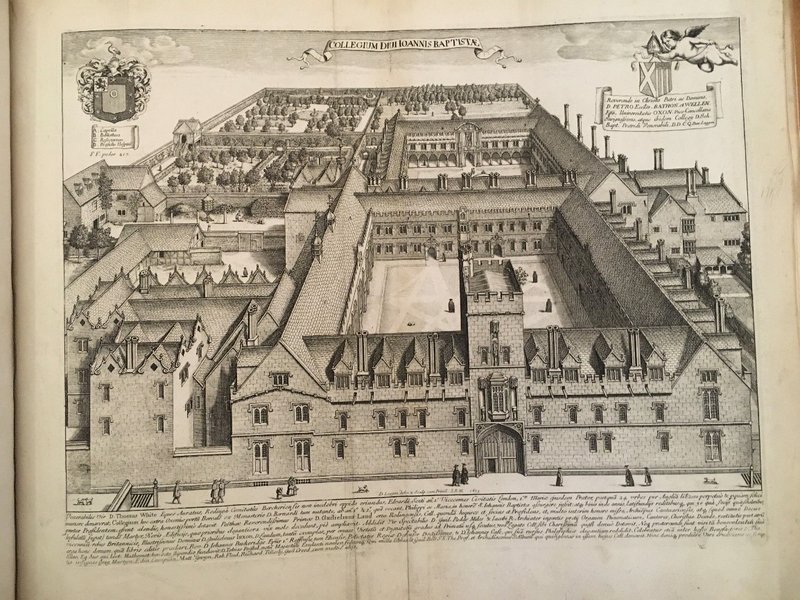

Did you know that the College gardens once contained a tennis court?

Courts for tennis and bowling appear to have been established c. 1620. Heavy expenditure was incurred for their maintenance, with College spending £19. 8s. 4d (approximately £3,8400 in 2024) on its ‘Spheristia’ (ball courts) in 1639.*

The courts were likely situated in the north-west corner of the Outer Grove (Great Lawn). David Loggan’s 1675 bird’s-eye engraving of College features a structure in this location that could well be the courts.

However, no such court appears in William Williams’s 1733 illustration of the College gardens in Oxonia Depicta. Is is thus likely that the courts were only in existence for a century.

(St John's, as depicted in David Loggan's Oxonia Illustrata, published in 1675.)

References and Further Reading

* W.C. Costin, The History of St. John's College Oxford: 1558-1860 (Oxford, 1958), pp. 95-96.

Did you know that former College President, Archbishop William Laud (1573–1645), was the first known owner of a pet tortoise in Britain?

According to Laud’s biographer, A.C. Benson a thigh-spured tortoise (Testudo graeca) was given to him during his time at St John’s, sometime between 1589 when he joined as a scholar and 1621 when his presidency ended. It is very possible that this reptile was the first presidential pet.

Regardless of when exactly Laud acquired his tortoise, it certainly outlived him. After the Archbishop’s execution in 1645, the tortoise remained in the garden of Lambeth Palace for over a century, its sedate munching uninterrupted by the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the reigns of six monarchs, from Charles II to George II.

Laud’s tortoise lived at Lambeth until the mid–eighteenth century, when it met an uncertain fate. According to some reports, the tortoise was killed by a negligent gardener who prematurely disturbed the tortoise’s winter slumber. Other accounts maintain that the tortoise sadly drowned when the Thames burst its banks and flooded the Lambeth Palace gardens in 1753.

Uncovered in the Victorian era, the tortoise shell can still be seen in the Guard Room at Lambeth Palace.

(Archbishop Laud’s tortoise, Lambeth Palace, London.)

Further Reading:

A.C. Benson, William Laud, sometime Archbishop of Canterbury: a Study (London, 1887)

M. Ford, Intellectual Capital: Money and Mind at St John's College, Oxford (London, 2023), pp. 193-96.

Did you know that in August 1636, the newly-finished Laudian Library hosted a lavish feast for King Charles I?

The prodigious feast was organised by Archbishop William Laud to celebrate the opening of Canterbury Quadrange. Built at Laud’s direction and personal expense, the construction of the quadrangle cost £5,554 (£1,016,448 in 2024).

Five months after the construction was complete, Laud spent nearly half as much again — an astonishing £2,666 (£487,910 in 2024) – entertaining King Charles I, Queen Henrietta Maria, Frederick V, the Elector Palatine, his son Prince Rupert, and various courtiers at St John’s.

Laud’s extravagant menu mainly consisted of vast amounts of meat. Bucks, does, oxen, sheep, rabbits, capons, ducks, pheasants, turkeys, swans, and quails were served in such quantities that one guest questioned ‘where there co[u]ld be found mouthes to Eate it’.* However, the showstopper of the feast was undoubtedly a marzipan model of the entire hierarchy of the University Convocation created by the King’s Confectioner.

After gorging themselves in the library, the party adjourned to Hall where they enjoyed a performance of George Wilde’s play, Love’s Hospital. For his part, Laud claimed to be ‘most heartily glad’ when the ‘expenseful business’ was over.†

References and Further Reading

* George Garrarde's letter to Edward Lord Conway (4 September 1636), printed in A.J. Taylor, 'The Royal Visit to Oxford in 1636', Oxoniensa 1 (1936): 151-58

† Laud's correspondence, quoted in H.R. Trevor-Roper, Archbishop Laud: 1573-1645 (2nd edn., London, 1962), pp. 288-94.

H. Colvin, The Canterbury Quadrangle: St John's College (Oxford, 1988), pp. 12-14

Did you know that the Baylie Chapel at St John’s holds an eighteenth-century heart?

The heart belongs to Richard Rawlinson (1690–1755), the antiquarian and nonjuring bishop. Both he and his older brother, Thomas, studied at St John’s, with Richard earning his BA in 1711 and proceeding to an MA in 1713. After completing his degrees, Rawlinson kept his rooms at College, using them as his primary residence until 1716. He frequently returned to Oxford thereafter to continue his research at the Bodleian.

When he died in 1755, Rawlinson divided his substantial collection of books and manuscripts between the Bodleian and St John’s. The Bodleian received his manuscripts and some of his printed books, while St John’s was gifted much of his property, along with several books, coins, and medals (now held by the Ashmolean Museum). Rawlinson’s benefaction remains one of the largest the College has ever received.

Following Rawlinson’s wishes, his heart was placed in a marble urn in the Baylie Chapel at St John’s, where it still rests. The rest of his body is buried at St Giles Church, just over the road from College.

Further Reading:

M. Clapinson, 'Rawlinson, Richard (1690-1755)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/23192

Did you know that Dolphin Quadrangle was built on the site of a former inn?

There is evidence that a brewery was in operation at the site of the Dolphin Quadrangle from the early sixteenth century. Known as the Dolphin Inn from c.1575, the brewhouse operated for nearly 130 years. The Dolphin was apparently a familiar haunt of St John’s dons. According to President John Mabbott (1963–69), the Inn ‘was reputed to have had a back door always open to the Fellows of St John’s, and a bedroom for any occasional mistress’.* By the time the Inn closed its doors in the late eighteenth century, it had also apparently acquired a reputation for hosting bull-baiting contests.

The Dolphin Inn was demolished c.1794. Houses were built in its place, and were purchased by St John’s for undergraduate lodgings in the 1870s. Latterly, the buildings and outhouses were converted to student baths which had a ‘gruesome’ reputation amongst College students.† Dolphin Quad as we know it today, with it’s Ionic columns and grand bike shelters, was built in the late 1940s.

(Dolphin buildings, c. 1875)

References and Further Reading:

* J.D. Mabbott, Oxford Memories (Oxford, 1986), p. 110.

† Correspondence of R. Hart-Synot (Bursar), quoted in G. Tyack, Modern Architecture in an Oxford College: St John's College 1945-2005 (Oxford, 2005), p. 11.

H.E. Slater and J. Carter, Oxford City Properties (Oxford, 1926), pp. 256-61.

https://www.oxfordhistory.org.uk/stgiles/tour/east/02_04.html

Did you know that the last person to be buried in the St John’s crypt was the College’s twenty-fourth President, Philip Wynter?

Wynter died in 1871, having served as the President of St John’s for 43 years, making him the longest serving President in the College’s history. Wynter was interred beneath the Baylie chapel shortly thereafter, after which the College crypt was not opened again until July 1996.

The crypt was last opened in 2024. Descent into the crypt was undertaken by the President (Sue Black – forensic anthropologist), Elizabeth Macfarlane (Chaplain), Ian Stokes (Works Bursar) and Rev Professor William Whyte (Professor of Social and Architectural History).

Little is known about President Wynter, save only that his children may once have used the Laudian Vestments as props during games of charades.

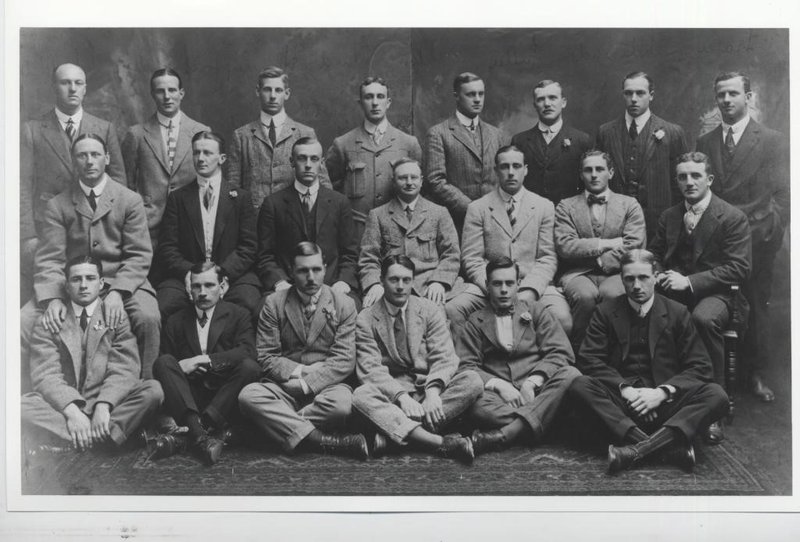

Did you know that a St John’s alumnus captained the first British & Irish Lions tour to Argentina in 1910?

The British & Irish Lions are a touring team consisting of the best rugby players from England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. In 1910, the Lions embarked on their first tour to Argentina, captained by England full-back and St John’s alumnus, John Edward Raphael.

The Lions played six matches during the tour, beating the Argentine national team 28–3 in ‘Los Pumas’ first ever Test match. Since 1910, the Lions have played six further Tests against Argentina, with a further Test to be played in June 2025.

During his time reading history at St John’s, Raphael won Blues in 4 sports: rugby, cricket, water polo, and swimming. He was also an enthusiastic and accomplished swordsman. He also wrote a fascinating treatise on Modern Rugby Football, which is available in the College Library.

Raphael was one of the earliest volunteers to join the British Army in 1914. He died in Belgium following the Battle of Messines in June 1917. He is memorialised at St John’s and OURFC.

(1910 Touring Team)

Further Reading:

J.E. Raphael, Modern Rugby Football (London, 1918)

M. Hagger, 'Remembering John Edward Raphael', RFU Web Article.

E.G. Saenz, 'The 1910 British & Irish Lions Tour of Argentina', World Rugby Museum.

Did you know that during WW1, St John's established a school for Belgian refugees?

Between 1914 and 1915, 200,000 Belgian refugees arrived in Britain. Oxford was one of many cities to welcome the refugees and to offer lodgings and employment to Belgian expatriates.

On 10 March 1915, St John’s Governing Body agreed to establish a school for Belgian children in the Old Lecture Room. (Unfortunately, the exact location of this room within College remains a mystery.)

Classes began shortly thereafter, taught in French by Belgian schoolmasters. The school appears to have operated continuously throughout the war, with College’s Governing Body agreeing to provide new furniture for the students as late as October 1918.

(Belgian refugees photographed in Canterbury Quad)

Further Reading

J.M. Winter, 'Oxford and the First World War', in The History of the University of Oxford: Volume VIII: The Twentieth Century, ed. B. Harrison (Oxford, 1994): 2-25

Interview with Michael Riordan, College Archivist, BBC - World War One At Home.

Did you know that during the Second World War, the North Quadrangle became the biggest fish and chip shop the world has ever seen?

During the war, St John’s shared its buildings with civil servants from the Ministry of Food. Whether intentionally ironic or not, the controllers of fish and potatoes were billeted together in North Quad, leading the historian Peter Hennessy to describe ‘this ancient seat of higher learning [as] the biggest fish and chip shop the world has ever seen’.*

As the wartime government dispersed key personnel and institutions away from London, it was not uncommon for Oxford colleges and University buildings to be requisitioned: Merton was taken over by the Ministry of Transport and St Hugh’s was converted to a hospital for head injuries.

(North Quad Tower, 2024)

References and Further Reading:

* P. Hennessy, Whitehall (London, 1989), p. 115.

P. Addison, 'Oxford and the Second World War', in The History of the University of Oxford: Vol. VIII: The Twentieth Century, ed. B. Harrison (Oxford, 1994): 166-88.

Did you know that the architect’s brief for the Thomas White Buildings originally included a swimming pool?

In the mid-1960s, St John’s faced a dramatic housing shortage. As College contemplated building on the site to the north of North Quad – then the President’s vegetable garden – the Building Committee prepared an ambitious brief for four competing firms. College requested accommodation for 30 married and 90 unmarried students, a house and two flats for Fellows, a lecture room for 160 people, a new MCR, a science library, an underground carpark for 100 cars, a dining room for 100 people; a porter’s lodge; and an indoor swimming pool.

The pool was noted as desirable, but not essential, and it was eventually dropped from the brief in April 1968 after a review of the costs associated with the project.

Before the designs of Philip Dowson of Arup Associates were approved in December 1971, College’s plans had changed dramatically. Concerns over the environmental impact of car travel, and the cost of underground excavation, led to the cancellation of the car park. The proposed dining room was also temporarily shelved, only to be revived when Garden Quad was built twenty years later.

Further Reading

G. Tyack, Modern Architecture in an Oxford College: St John's College 1945-2005 (Oxford, 2005), pp. 43-81.