Chiara Betti brings to light the Rawlinson copper plates at the Bodleian Library

Following a quarrel with the London Society of Antiquaries, Richard Rawlinson left most of his printed books, manuscripts, and all his printing plates to the Bodleian Libraries. His extensive estates went to St John's College.

Following a quarrel with the London Society of Antiquaries, Richard Rawlinson left most of his printed books, manuscripts, and all his printing plates to the Bodleian Libraries. His extensive estates went to St John's College.

While there has been a constant interest and much research on Rawlinson's books, the copper plates have been awaiting further studies for centuries. Thanks to funding from UKRI, the Rawlinson copper plates are now at the centre of a Collaborative Doctoral Partnership project jointly supervised by the Institute of English Studies (University of London) and the Bodleian Libraries.

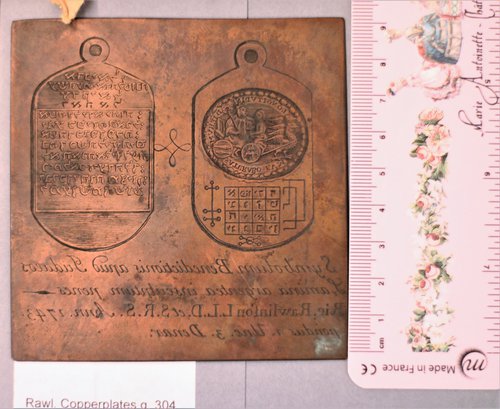

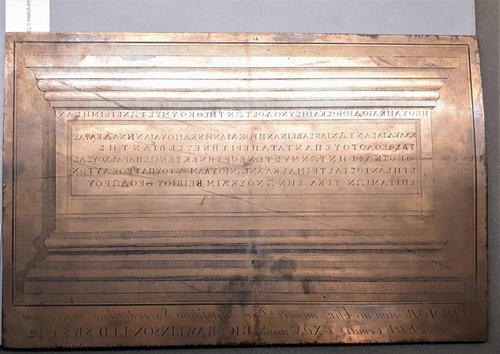

During his life, Richard Rawlinson built a collection of about 750 printing plates. A good portion of them was made to illustrate his vast collections, and Rawlinson commissioned them to famous engravers like George Vertue and Michael Burghers. The rest of the plates were purchased at auction sales. The copper plates illustrate various subjects: portraits, facsimiles of documents, topographical views, coins, medals, and seals. However, few plates do not fit into any of the above categories, like the printing plate for a folding fan, a true gem, or those for trading cards.

With pioneering attention to divulgation, Richard Rawlinson made the most of the possibilities offered by engraving. Printing facsimiles of documents and reproducing the objects in his collections was more straightforward and cheaper than shipping the real objects to the fellow collectors who enquired about his specimens. Therefore, since the early 1720s, Richard Rawlinson ordered engraved plates that he printed and circulated among his many correspondents and the Society of Antiquaries. Had he not reproduced his most precious curiosities through burin and copper, today we would not know about his ivory chalice and Jewish silver amulet now dispersed.

Besides commissioning original engravings, the voracious collector attended many auctions of books, art, and copper plates. Even when his health did not allow him to participate in person, he kept buying through his agents, continuing to purchase until the last days of his life. Thanks to Rawlinson's meticulously annotated sales catalogues, we can now study his purchasing habits, the price of the second-hand copper plates, and identify the attendees to auction sales. For instance, the Caldwell & Glass sale catalogue (1751) at the Bodleian Libraries contains annotations of the sale price of each lot and often the name of the successful bidder.

Despite Thomas Hearne's scepticism on Rawlinson's ability to transcribe inscriptions, Richard Rawlinson's copper plates were appreciated and sought after by many antiquaries such as William Brome and Thomas Wilson. Numerous scholars also often offered their help to translate Hebrew or Greek inscriptions (see right). In their letters, those collectors frequently praised Rawlinson's efforts to making his resources publicly available. In fact, in a letter to Bodley's Librarian Humphrey Owens, Rawlinson expressed the worry that his marbles, donated to the Bodleian, might end up "closetted up" and hidden from public view.

In his will, Richard Rawlinson's specified that his copper plates were to be 'by them [the University] worked off into one volume, and the impressions to be sold for their use and benefit.' However, this never happened due to the lack of a rolling press at the University at that time. Nonetheless, the correspondence between the Librarian and scholars continue to show a keen interest in Rawlinson's plates until the late 18th century. For instance, the copper plate illustrating St Giles' Church, Oxford, was used in John Peshall's edition of Anthony Wood's City of Oxford in 1773, almost twenty years after the bequest.

Then, for over a century, the interest in the Rawlinson plates seems to have petered out until, at the beginning of the 20th century, Ms Edith Guest compiled a handlist of the copper plates. Ms Guest catalogued them according to their size, separating series of copper plates that should have stayed in a sequence. In the early 1920s, the Bodleian Library, possibly short in storage space – less than 80 years earlier, received some 19,000 volumes and over 25,000 prints from the Douce bequest – tried to transfer the copper plates to the Clarendon Press first and then to the Oxford University Press. Needless to say, those attempts failed, and the printing plates continued to lie undisturbed in the Library's storage until Dr Enright wrote his thesis on Richard Rawlinson in 1957, in which he included a list of the plates commissioned by Rawlinson.

This blog is a brief introduction to the research project that started in October 2020. This innovative research aims to study the history, provenance, and manufacture of the Rawlinson plates for the first time. Several of the primary sources documenting the plates' production are at St John's College, which will hopefully benefit from the doctorate's discoveries. The Rawlinson copper plates are an unparalleled corpus of artworks, as no other private collector has ever gathered as many matrices as Rawlinson. Thanks to the antiquary's obsession for preservation, this project will finally shed light on collecting and printing practices in 18th-century Britain.

This blog is a brief introduction to the research project that started in October 2020. This innovative research aims to study the history, provenance, and manufacture of the Rawlinson plates for the first time. Several of the primary sources documenting the plates' production are at St John's College, which will hopefully benefit from the doctorate's discoveries. The Rawlinson copper plates are an unparalleled corpus of artworks, as no other private collector has ever gathered as many matrices as Rawlinson. Thanks to the antiquary's obsession for preservation, this project will finally shed light on collecting and printing practices in 18th-century Britain.

For more information on other collections of copper plates at the Bodleian Libraries please visit Printing Surfaces libguide.

Chiara Betti, doctoral student at School of Advanced Study, University of London