2. Richard Rawlinson: benefactor, antiquary, and beneficiary of British colonialism (Part 1 of 2)

Rawlinson’s estates, willed to the College, constituted perhaps its biggest benefaction after that of its founder, Sir Thomas White. Rawlinson’s books and manuscripts left to the Bodleian Library form one of its richest collections, he was the founder of the university’s Anglo-Saxon professorship (known as the Rawlinson Professorship until 1916 when it was renamed the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship) and held by a long line of illustrious philologists and scholars of Old English, including J.R.R. Tolkien.

Rawlinson’s connection with the British empire and the slave trade is indirect but vivid and many-sided, entangled but clearly discernible. This post represents a brief but tantalising glimpse of a fascinating history through a rough sketch of what little we have had time to explore. Even so, the importance of Rawlinson to St John’s and the intricate complexities of his connections with colonialism mean that we will need to publish this post in two parts, this being the first.

Richard Rawlinson was born in 1689 or 1690, into a prosperous, well-connected family with a name, ancestral property and coat of arms apparently stretching back to Henry V (reigned 1413-1422) and Agincourt (1415). We have this information about the family, as well as several other details on the Rawlinsons from a 1990 book published on Richard Rawlinson by a Rawlinson descendant, Georgian Rawlinson Tashjian and her husband David Tashjian, based partly on their own research and partly on a PhD thesis by Brian J. Enright. Thomas Rawlinson Senior, Richard’s father, was a man of substance from a family of successful tea merchants and vintners (wine-merchants), respected and influential. He had been knighted by James II (r. 1685-1688) in 1686, and held positions of high public office, culminating in being made Mayor of London in 1705, when Richard was 15.

One of fifteen children, Richard and his brother Thomas were the only ones amongst his siblings to be given a privileged education, at St Paul’s School (next to the Cathedral, then being rebuilt by Christopher Wren), Eton College, and St John’s College, Oxford. Both attended Oxford as Gentlemen Commoners (a class of undergraduates who paid higher fees and had special privileges), had rooms in the college’s envied Canterbury Quad, and presented the college with a piece of silver in return for the right to dine at the Gentlemen Commoners’ Table in Hall. Though Richard’s tankard has been unfortunately lost, his brother Thomas’s, engraved with the College’s and the Rawlinson family arms, is still brought out and used for College Feasts.

The Rawlinsons had made their money in trade, and much of it by trading in East India tea. At least one son, Daniel, elder to Richard by three years, was on his way to India, almost certainly to join the East India trade, when he contracted an illness and died on board ship. We know this from a Latin inscription on a memorial made for Thomas Senior in a church in London. The church was destroyed in the nineteenth century and the memorial is gone, but a handwritten copy of the inscription is amongst Rawlinson’s papers at SJC. When Sir Thomas Rawlinson, Richard’s father, died, he left £12,000 (a vast sum of money) in the form of East India stocks (Rawlinson, Sir Thomas, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). Their father’s will left Richard and his siblings if not excessively rich, comfortably provided for, with Richard, his four surviving brothers and three sisters each receiving £1000 pounds upon reaching the age of twenty-one (or in the case of the women, if they were to marry before turning twenty-one, then upon their marriage). This was enough to ensure each of the Rawlinson children had access to an independent income.

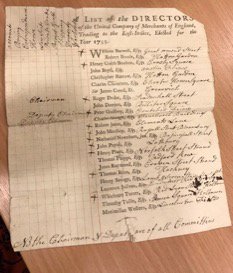

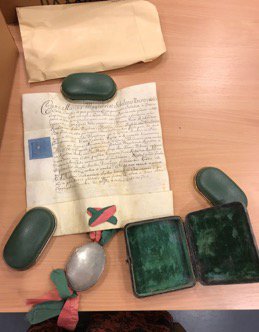

It seems, moreover, that Richard himself retained some kind of interest in the East India Company even after his father’s death: among his papers survives a printed list of Directors of the East India Company (right) – a number of names are marked out by crosses penned beside them as well as handwritten addresses – presumably of where they lived or had their offices. In addition, Richard’s mother’s Will (left), which carefully lists each of her surviving children and those of her own personal possessions she had chosen to leave to them, explicitly mentions Richard as the inheritor of his mother’s East India tea chest and ‘a silver medal struck with the arms of the East India

Company’. None of the other objects listed or left to Mary Rawlinson’s other children have any connection with the East India trade. Both pieces of evidence suggest a continuing connection between Richard and the East India Company that we do not yet know enough to be certain of, or know the details.

Richard matriculated (formally entered the University) at St John’s College, Oxford, in the academic year 1707-1708, and received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1711. But he retained his rooms in College, and continued to use them as a main residence until 1716, returning often to Oxford to pursue his researches at the Bodleian Library. By the time he had completed his undergraduate studies at Oxford, Richard - encouraged by his older brother Thomas who was a prominent book collector, and Thomas Hearne, assistant keeper at the Bodleian, a well-respected scholar, diarist, editor of medieval manuscripts, and lifelong friend of both brothers - had discovered a lasting fascination with old books and printed materials, medieval history and antiquities.

In 1716, Richard Rawlinson was ordained as a priest and later a made a Deacon, but in both cases as a Non-Juror (therefore he was not ordained into the Church of England in the ordinary sense). Rawlinson’s political and religious convictions prevented him from being formally recognised or holding any state or religious office. The Rawlinson family were intensely loyal to the reigning Stuart dynasty, and when James II left the country in 1688 without abdicating from the kingship, the Rawlinsons, like other families with similar convictions, continued to recognise him as their King, and Head of both Church and State. Despite several attempts, James II did not return to the throne. Nor was his son James III (as he would have been considered by Rawlinson) - the Old Pretender (as he was generally known), or grandson, Charles Edward (the Young Pretender), any more successful. Meanwhile, the Protestant Prince William of the Dutch Republic, husband of James’ daughter Mary, was invited to take the English throne. On his accession, William (who reigned as William III) required an oath of loyalty, recognising him as head of both Church and State, to be sworn by all who held any official position in the State or Church. Those refusing to do so were liable to lose their position, if they had one, and were prevented from holding any, if they did not. Richard Rawlinson, and others like Richard, who remained loyal to James and the Stuarts and would not accept William, were known as Non-Jurors, and being unable to earn their livelihoods through public office, were largely engaged in private enterprise or activities such as book-collecting. Rawlinson’s political convictions would lead him into acrimonious disputes, but was in the end A Good Thing for St John’s and Oxford, since it resulted in Rawlinson disinheriting his other principal beneficiary, the Society of Antiquaries, and leaving the bulk of his estates, with a small exception, and his valuable collections, to his College and his University. This choice was no doubt helped by the fact that both at this time retained largely Jacobite sympathies and St John’s in particular, had a long connection with Charles I, and had been Archbishop Laud’s college.

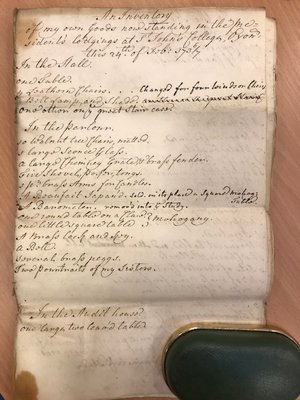

Richard Rawlinson had continued to be attached to both Oxford and St John’s throughout his life. He never married, and as noted, he maintained his rooms in College for several years after his BA. Toward the end of his life, he once again hired rooms in College, primarily to store his by now vast collections of books and manuscripts. He even left a quantity – enough to furnish a reasonable-sized house – of furniture, carpets, paintings, pots and pans in the President’s Lodgings (rooms reserved for the Head of the College) at St John’s. An inventory of these items (right) is preserved in the SJC archive, though we don’t know if they were eventually collected, or disposed of, or if some remain even now dispersed through the College, hidden in plain sight!

Sir Thomas Rawlinson died in 1708, soon after Richard entered university. His death left Richard with a comfortable independence but also laid financial and familial responsibilities at his door, as he proceeded to manage and attempt to guard the family fortunes against various profligate and (from Richard’s point of view anyway) ill-judged actions by various members, particularly their mother Mary Rawlinson who proceeded to marry again, twice. Her marriage settlements and separations from both husbands placed heavy burdens on the family coffers and resulted in legal action taken by Richard and his siblings against their mother and her (respective) husbands. While still studying at Oxford Richard had begun to publish papers in antiquarian journals, and in 1714 was elected to the Royal Society at the age of twenty-four or five. In 1716, after his ordination, Richard had moved to Gray’s Inn, London, where he continued his scholarly activities, and in 1719 he returned to Oxford to take the degree of

DCL (Doctor of Canon Law). His doctoral degree certificate and seal are preserved in the SJC archive (left), and are an impressive sight - in high contrast to the mere sheet of paper that signifies an Oxford doctoral degree in the present day!

In 1720, Rawlinson left England for an extended and expensive tour of the continent which lasted nearly six years.The European Grand Tour was considered an almost mandatory experience to complete the education of a young man of birth and breeding. However, Rawlinson's European travels were not undertaken as a Grand Tour generally was - as a form of social education or a kind of aristocratic finishing school, but rather to pursue his study of liturgy, art and antiquarianism and to follow the Jacobite trail. Richard’s relative wealth is also demonstrated by the fact that he was able to lend his brother £3000 pounds - a considerable sum, soon after their father’s demise. During his years in Oxford and London, Richard had been in close contact with his older brother, Thomas, and was often in his London lodgings, exchanging notes on books and manuscripts, discussing scholarly papers and accompanying his brother to sales and auctions. After his departure from England, and travelling as he was from place to place, Richard was no longer in regular contact with his family, and lost sight of his elder brother’s affairs.

Thomas Rawlinson Jr., being the eldest son of Sir Thomas, was his father’s primary heir, and inherited the family estates – consisting of extensive lands and properties. However, Thomas Jr. lived well beyond his means, and was frequently, and finally irrevocably in debt. Like a large cross-section of the population, Thomas Rawlinson Jr. had invested in the South Sea Company, a joint-stock business venture floated by a group of businessmen and politicians which was intended (or so the Company claimed) to reduce the national debt in a few short years. A vast number of British people, rich and poor, invested and lost their money through what came to be called the South Sea Bubble, which ‘burst’, in 1720, amongst these was Thomas Rawlinson Jr. The interest for us lies in the fact that the South Sea Company was contracted to supply slaves to Jamaica, which was to be source of a large part of its profits. In the end the Company made enormous losses and its shares fell rapidly ruining most of its investors, and impoverishing the unhappy Thomas, yet the connection between Rawlinson family capital and British investment in the slave trade remains. Interestingly, it appears that Richard Rawlinson was strongly opposed to the slave trade, but further discussion of this must wait for the second part of this blog post!

Dr Mishka Sinha