July 2022

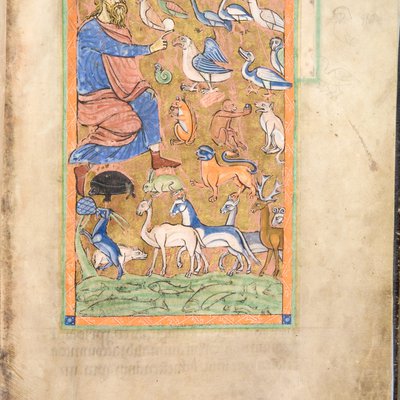

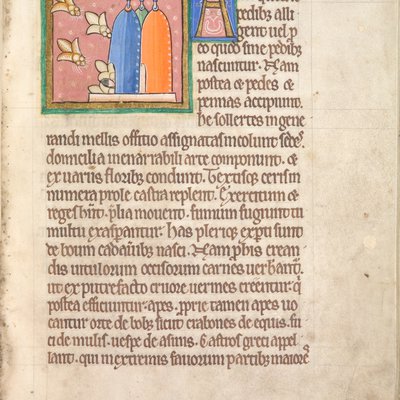

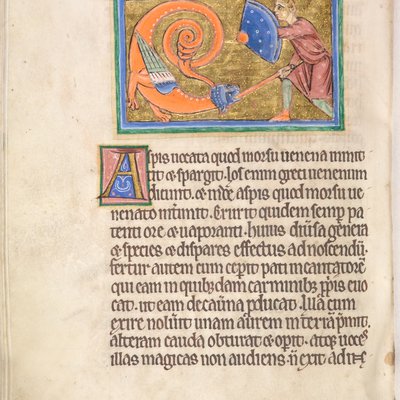

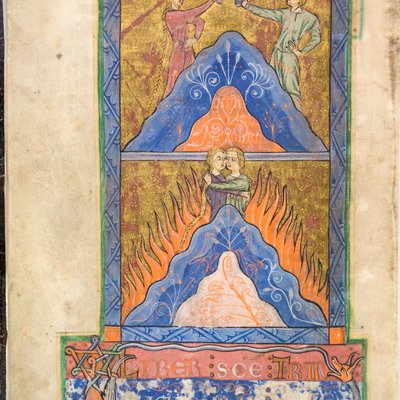

Now that the summer is in full swing, and flora and fauna enjoy the warm season, why not celebrate this time of the year medieval style? The so-called “York Bestiary” is a firm favourite with library staff and visitors. Who can resist these charming, often funny and sometimes puzzling illustrations of animals together with a dazzling display of gold?

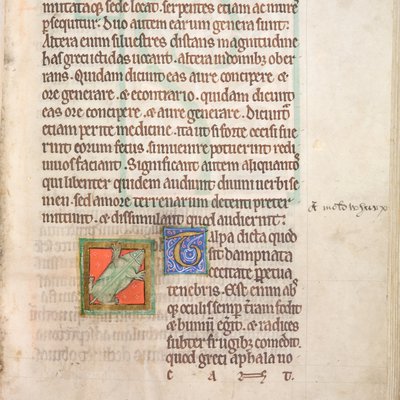

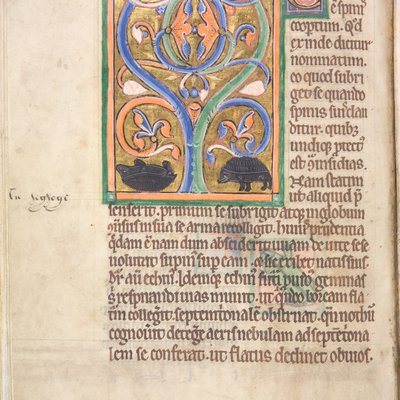

Bestiaries are a combination of natural philosophy passed down the centuries with Christian allegories and morals. The hedgehogs, for instance, are said to shake off fruits (mostly grapes from vines as in our manuscript, but variants also name apples or figs). They then roll on the fallen fruit to pick them up with their spines. This allows them to carry the fruit to their offspring as food (Badke). In Christian allegories the hedgehogs’ behaviour warns of “the clever stratagems of the devil in stealing man’s spiritual fruits” (Spillane). Medieval bestiaries also pick up what is arguably the best-known fact about hedgehogs today: at the sight of danger they roll themselves into a ball and rely on their spines to protect them.

Bestiaries have a long tradition, going all the way back to the 2nd-century CE Greek Physiologus. They were such popular illustrated books in the Middle Ages that manuscripts survive in a relatively large number and a variety of languages. The York Bestiary is part of the so-called “second family” of medieval bestiaries, which includes most surviving copies. Their contents are based primarily on Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae but also exhibit significant material from, among others, Ambrose, Rabanus Maurus, and Solinus, the latter, in turn, relied heavily on Pliny (Badke).

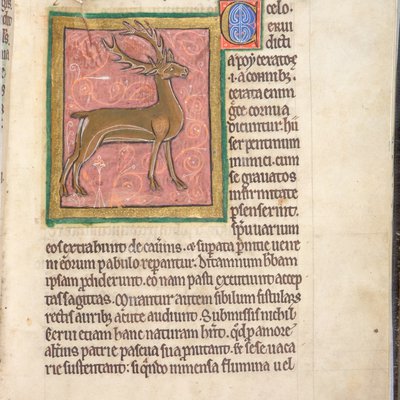

Many illustrations of the animals in MS 61 are accompanied by their respective English names in a late 15th-century script. The Latin word for ‘hedgehog’ is (h)erinacius (also ericius as in our manuscript) and the Middle English is heyghoge, here spelled heyhoge. For the ‘mole’, Middle English knows both molle and moldwerp (and variants thereof, here moldwharp), the literary translation of the latter term is ‘earth-thrower’.

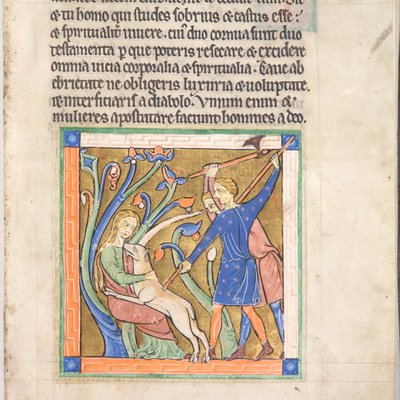

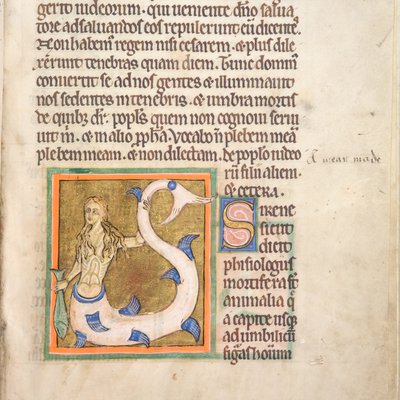

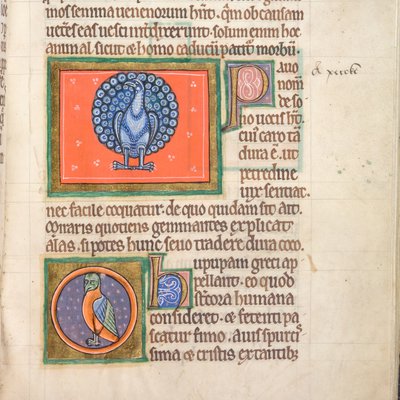

Like other bestiaries, the York Bestiary includes fantastical creatures, such as the griffin, mermaid, phoenix, and unicorn. Our manuscript distinguishes the unicorn from another one-horned beast, the monochornus. The illustration shows the myth that the unicorn can only be captured if it lays its head into the lap of a virgin. In contrast to today’s exclusively equine depictions of unicorns, in medieval bestiaries it also appears as a goat or a donkey (Badke). In contrast, the monochornus is a dangerous beast with the body of a horse, the feet of an elephant, and, sometimes, the head of a deer (Badke). Interestingly, the term rhinoceros, which is today used for an altogether different and not mythical animal, is presented as a synonym of the term ‘unicorn’.

The York Bestiary is believed to be a product of the Benedictine Priory Holy Trinity in York. Indeed, it is the only known surviving book from this house (Raines). A parish church today, Holy Trinity is listed in the Domesday Book as one of the five great churches of the North together with the Minsters of Beverley, Durham and Ripon, and York Minster (Raines). Between the mid-14th century and 1536 the York Mystery Plays started outside Holy Trinity before moving across the city. The monks’ library must have suffered the same fate as that of most other monastic libraries during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the books were either destroyed or dispersed. It is not known how the York Bestiary ended up in the possession of William Paddy, Royal Physician and Fellow of St John’s, who bequeathed it to the College in 1634. It would not be the only spoils of the Reformation that ended up in St John’s College’s historic collections.

To find out more about St John’s College’s historic collections, visit us at https://stjohnscollegelibraryoxford.org/ or follow us on Twitter @StJohnsOxLib.

As it happens, our York Bestiary is now fully catalogued online at Medieval Manuscripts in Oxford Libraries. You can find the link to this and other online manuscript records in our Digital Library at https://stjohnscollegelibraryoxford.org/digital-library/western-medieval-manuscripts/.

References

- Badke, David, The Medieval Bestiary, at www.bestiary.ca [accessed 29/01/2022]

- Raines, Dick, and Sue Raines, ‘History & Monks of Mickelgate Exhibition’, Holy Trinity Mickel gate, at https://www.holytrinityyork.org/history/monks-micklegate-exhibition [accessed 29/01/2022]

- Spillane, Jodi, “How to Be a Hedgehog”, British Library: Medieval Manuscripts Blog (23 October 2014), at https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2014/10/how-to-be-a-hedgehog.html [accessed 29/01/2022]