November 2022

On 5 November, it is Bonfire Night again in memory of the failed attempt by a group of Catholics to kill King James I by blowing up the House of Lords on 5 November 1605, the so-called Gunpowder Plot. The public celebrated the king’s narrow escape with bonfires soon after those events. Nowadays, the occasion is not only celebrated with bonfires but also fireworks displays.

As a form of entertainment firework displays became popular in the Tudors era and reached an early peak during the Elizabethan Age (Kinchin-Smith). There were risks involved, however. In 1572, Robert Dudley presented a fireworks display for Elizabeth I at Kenilworth Castle when an error sent fireballs into the nearby town, burning down several houses and killing at least one person (Kinchin-Smith). In 1613, Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre famously burned down after a pyrotechnic effect had gone wrong.

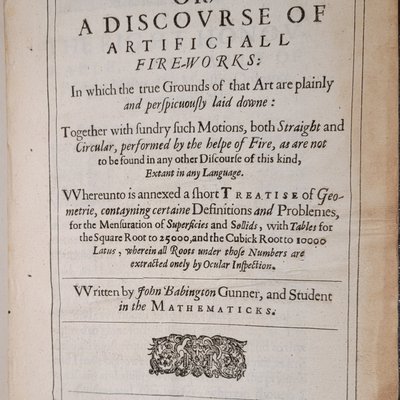

Fireworks enthusiasts must have been eager to read John Babington’s Pyrotechnia, or, A Discourse of Artificiall Fireworks, the first English-language book on how to produce fireworks for military use and entertainment, when it was published in 1635. Babington was a soldier (a gunner) and mathematician about whom virtually nothing is known other than he was a citizen of London and a member of the Salters’ Company (Anderson), one of London’s Livery Companies, trading in salts and chemicals for cleaning, dyeing fabric, softening leather etc.

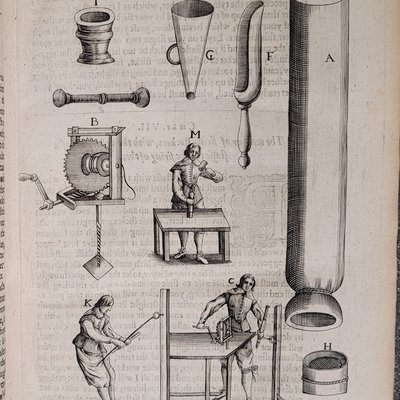

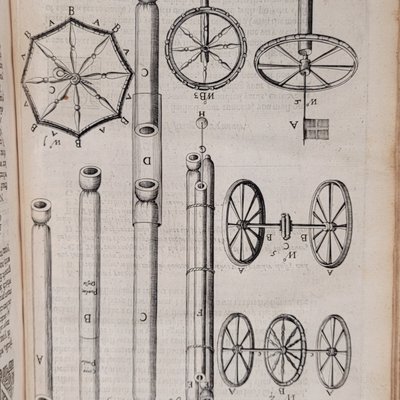

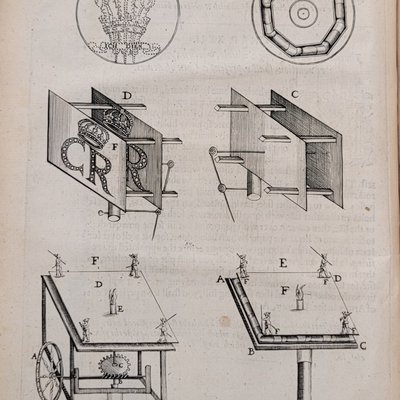

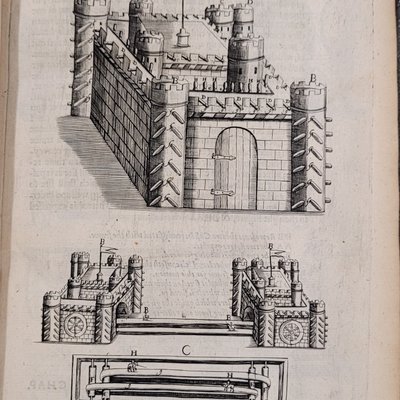

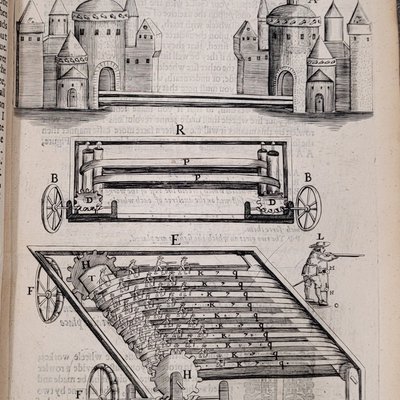

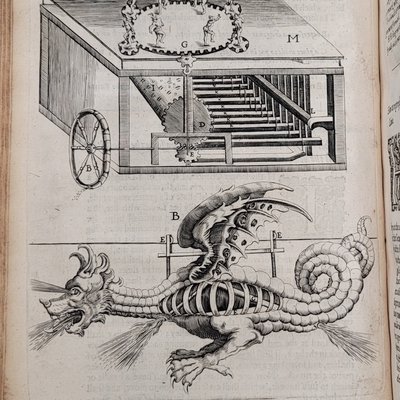

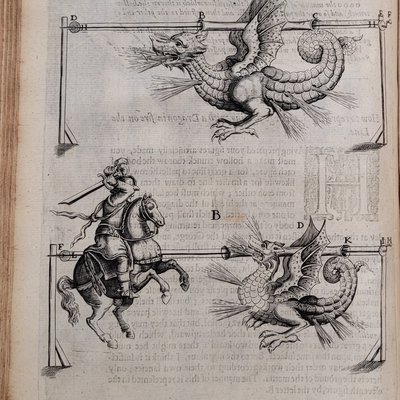

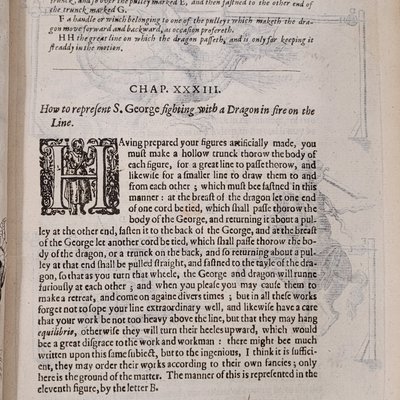

Pyrotechnia offers surprisingly detailed instructions accompanied by equally detailed illustrations. These include fireworks displays still familiar to us, namely rockets, Roman candles, wheels, and raining stars/colours. In addition, he described how to create fancier and more complex fireworks, such as representations of coats of arms, a Jack in the Box ('Iac in a box'), and castles of fireworks, and, last but not least, a mermaid playing on the water. My personal favourite are the dragons in various formats, including fire-breathing dragons emerging from caves, representations of St George fighting a fire-breathing dragon, or even a ‘dragon issuing out of a Castle, which shall swimme thorow the water and be incountered by a horseman from shoare’.

Interestingly, St John’s copy was donated to the library by none other than Archbishop William Laud. As there is no other ownership statement in the volume, it is tempting to amuse ourselves with the thought that he may have purchased this book in connection with his own duties to entertain royal visitors. The official opening of his ‘building’ as the calls Canterbury Quad with the Inner Library (today’s Laudian Library) in an entry of his diary, took place on 25 August 1636. On the occasion, Laud threw a banquet in the Inner Library for King Charles I and Queen Henrietta. We know the night’s entertainment included a play, but what else did Laud offer? Alas, there is no evidence of a fire-breathing dragon in the College garden, a mermaid on water, or even just raining silver and gold. Well, perhaps that was for the better – a repeat of the Globe Theatre pyrotechnic mishap at St John’s College does not bear thinking about.

If you’d like to know more about the festivities on 25 August 1636 at St John’s College, check out this blog post at https://stjohnscollegelibraryoxford.org.

References:

Anderson, R. E., “Babington, John”, revised by Anita Mc Connell, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, at https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/975 [accessed 12 October 2022]

Kinchin-Smith, “History of Fireworks”, English Heritage Blog Posts 5 November 2014, at https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/inspire-me/blog/blog-posts/history-of-fireworks/ [accessed 12 October 2022]

The Salter’s Company: Company History, at https://salters.co.uk/company-history/ [accessed 12 October 2022]