Dr Carolyn La Rocco: Female patronage in the late Roman and post-Roman west

Late Antiquity is a term we use to describe the period in the Mediterranean between the end of Classical Antiquity and the early medieval world. It falls between (roughly) 250 and 750 CE.

For a long time, scholars such as Edward Gibbon told the story of the western Roman Empire during this period as one of decline: it was often assumed that the Roman west rapidly declined with the ‘fall’ of the last (western) Roman emperor, Romulus Augustus, in 476 CE, and fell into a period of stagnation and chaos known as the ‘Dark Ages’.

This, however, is a misconception. In fact, Late Antiquity was a very complex and dynamic period, which saw various political changes across the post-Roman west: the growth of various kingdoms (for example, the Visigothic Kingdom in Iberia, or the Vandal Kingdom in North Africa). There were also significant cultural changes – Late Antiquity saw the rise of religions such as Christianity, Rabbinic Judaism, and Islam, and associated legal and cultural changes (and religious persecutions), as well as continued artistic and literary development.

The history of the late Roman and post-Roman west was also long told as a history of men- especially kings, generals, and bishops. This is due at least to some degree to the nature of the surviving primary sources, most of which were written by or about men: in many of these sources, the contributions of women are downplayed or attributed to men.

It cannot be attributed entirely to the evidence, however – many sources describe women of various backgrounds and social classes undertaking patronage or exercising their agency (especially economic agency) in other ways. Such women appear in Iberian sources like Ildefonsus of Toledo’s De viris illustribus and a letter eulogising the late Visigothic Queen Hildoara. There is abundant textual evidence in Gaul. According to the Gallic Vita Sanctae Genovefae, for example, Saint Geneviève sponsored a church in Saint-Denis in the mid-fifth century. Gallic noblewoman Magnatrude, Gregory of Tours’ Historia Francorum tells us, acted against her husband to maintain control of their property. Similarly, in England, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History documents seventh-century literary commissions and monastic patronage at Whitby by Queen Eanflæd and her daughter.

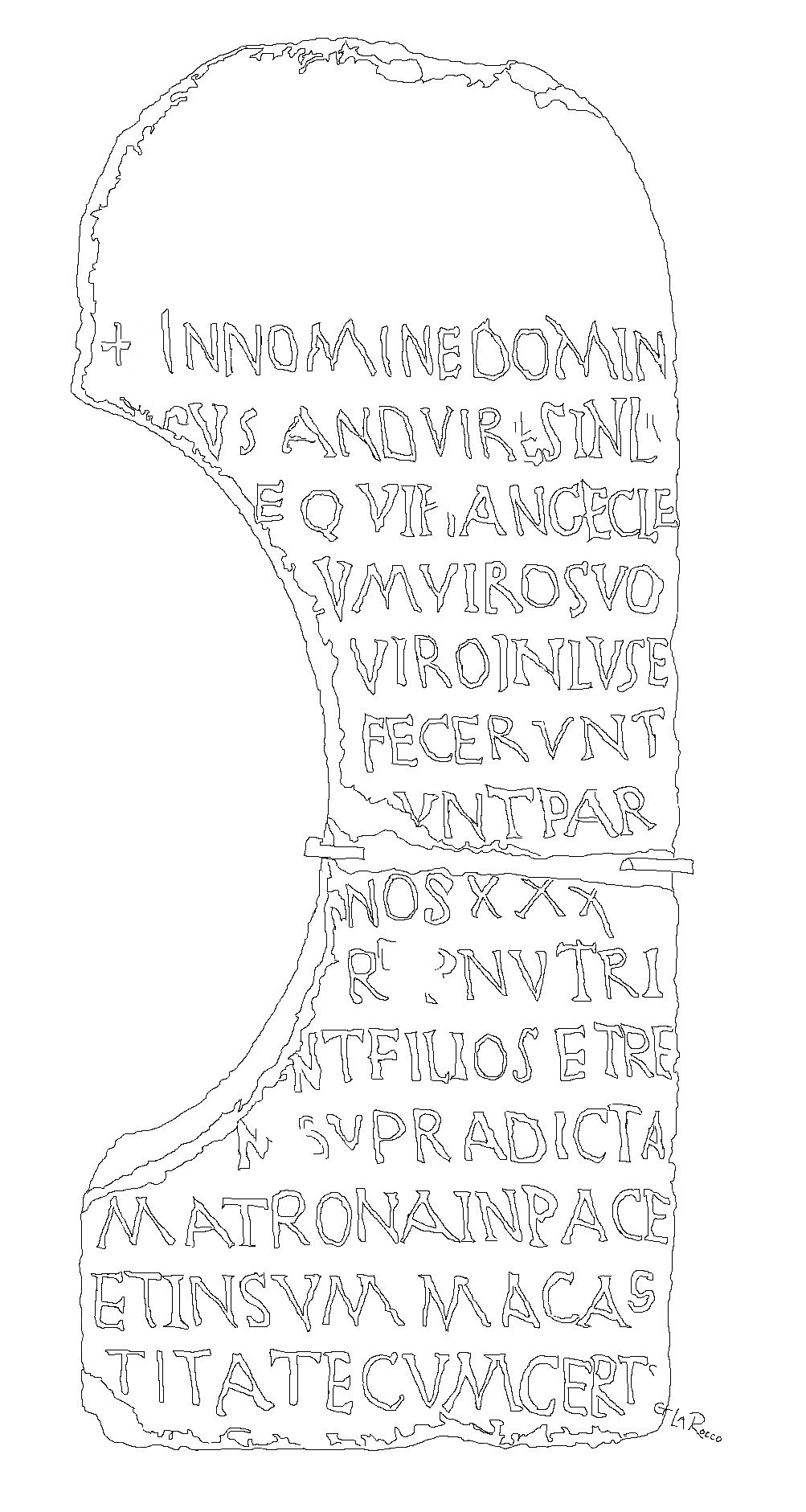

We also have material evidence. It takes various forms, but especially inscriptions – sometimes our evidence comes from inscriptions on tombstones, and much of it appears in dedicatory inscriptions commemorating women who were involved in founding or funding churches or other Christian spaces. The sixth-or seventh-century tombstone of a noblewoman named Anduires from in Soria in Castilla y León, for example, tells us that she founded a church alongside her husband: (‘Anduires inlis / [femina]e qui hanc ecle/[siam] cum viro suo / [And]uiro inluste / [---] fecerunt’ – ‘the illustrious woman Anduires, who built this church with her husband, the illustrious man….’).

Drawing of Anduires’ tombstone. Her tombstone is in the Museo Numantino in Soria.

Drawing of Anduires’ tombstone. Her tombstone is in the Museo Numantino in Soria.

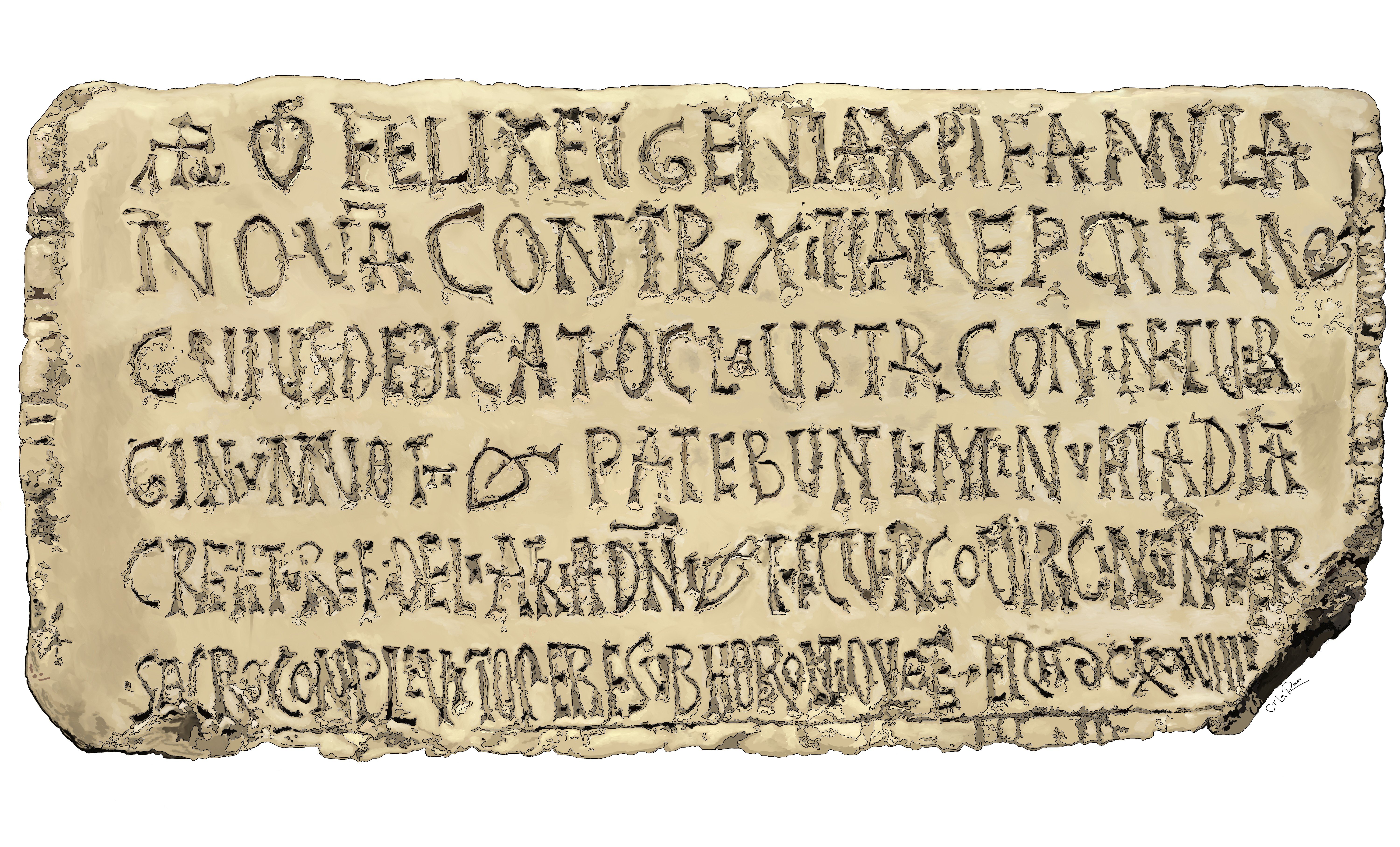

Likewise, an inscription from seventh-century Mérida documents the refurbishment of a convent by a woman named Eugenia, who is identified as an abbess (the inscription calls her ‘virgo virginum mater’, the ‘virgin mother of virgins’).

Drawing of the Eugenia inscription from Mérida. The inscription is in the Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid, Spain (Inventory Number 57768).

Drawing of the Eugenia inscription from Mérida. The inscription is in the Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid, Spain (Inventory Number 57768).

A woman named Iuliana funded an elaborate mosaic for a baptistery with her husband Aquinius and their children in Kélibia (قليبية ) in Tunisia in the late sixth century. The mosaic not only commemorates them, but is filled with intricate geometric patterns and imagery – dolphins, birds, flowers, fruit, and more.

The baptismal mosaic in Kelibia (now in the Bardo Museum). Image: Dennis G. Jarvis - Flickr: Tunisia-4812 - Demna Baptistry, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25176152

The baptismal mosaic in Kelibia (now in the Bardo Museum). Image: Dennis G. Jarvis - Flickr: Tunisia-4812 - Demna Baptistry, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25176152

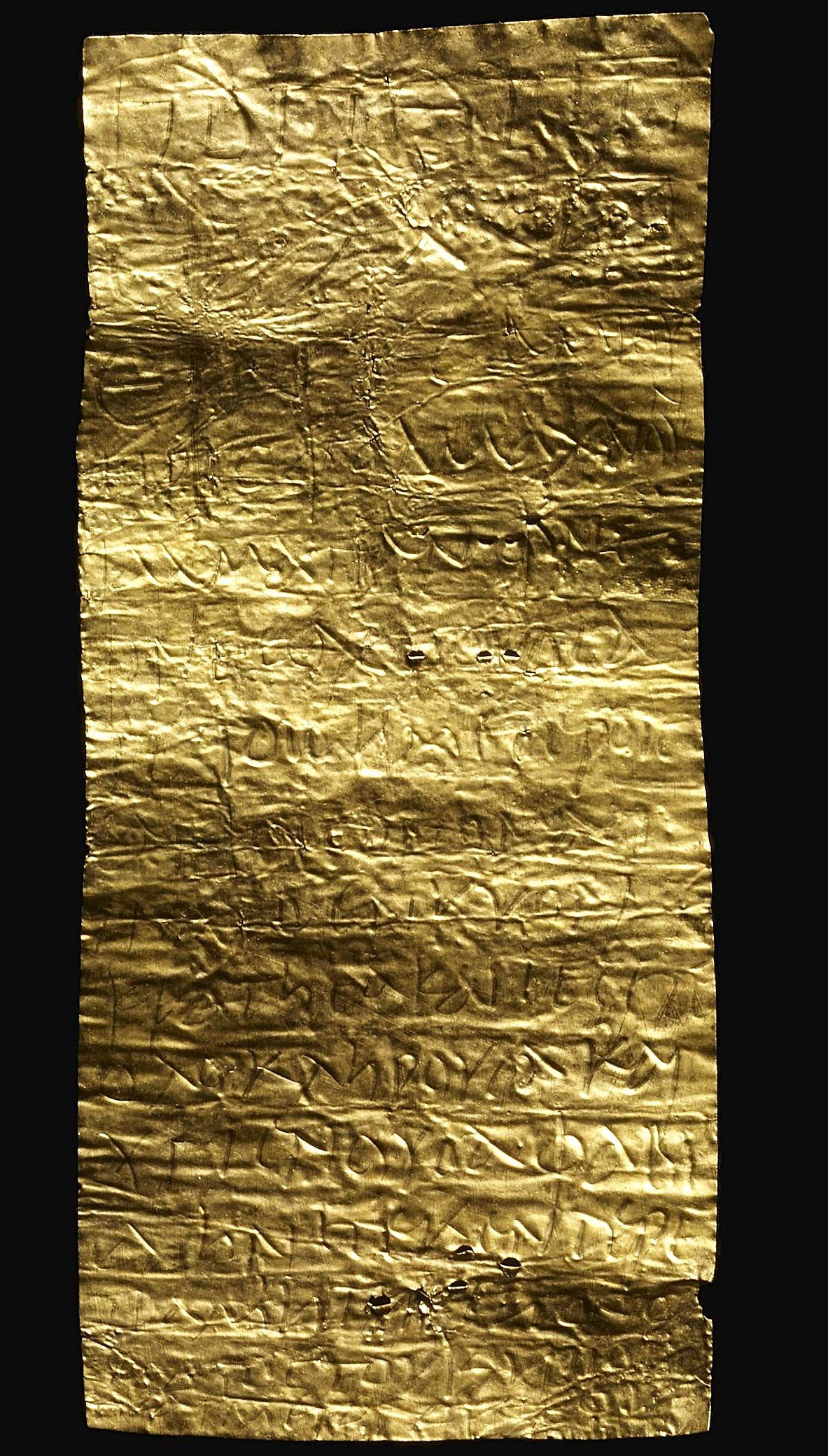

Other evidence comes from more private contexts. Some women appear in curse tablets (defixiones), cursing people who have stolen from them or wronged them in some way, as with the woman Saturnina, recorded in a lead ‘curse tablet’ from late antique Uley, England making an offering to the god Mercury (or, Mars Silvanus) if the god in question will return some linen that had been stolen from her. A gold foil amulet apparently belonging to a woman named Fabia, daughter of Terentia, was found in Cholsey (Oxfordshire, England). The tablet, said to date to the late Roman period, contains magical signs (charaktêres) followed by an inscription in which Fabia is wishing for a safe pregnancy and childbirth. While different in scale than an inscription, a church, a baptistery, etc., small finds such as these are no less important for our understanding of society in the late Roman and post-Roman west.

[[IMAGE 4]]

Fabia’s gold amulet in the British Museum (accession number 2009,8042.1). © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Fabia’s gold amulet in the British Museum (accession number 2009,8042.1). © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

These are but a few examples of the ways women around the late Roman and post-Roman west exercised their agency – there are countless other examples (textual and material). Despite this, women in prominent ‘broad strokes’ publications on ancient and medieval history today are still often either omitted, or flit in and out of focus, quickly mentioned as exceptional cases before attention returns to discussion of the actions of men. Even in instances where we have archaeological evidence telling us otherwise, the role of women is sometimes minimised in favour of the men who were involved. A Roman altar that was reused in the Visigothic period records a woman named Eulalia sponsoring the creation of a church with her son Paulus in Rute (Córdoba) – despite this, the inscription is commonly known as the ‘Altar of Bacauda’, the bishop who consecrated the church.

Viewing the ancient and medieval periods without fully considering and acknowledging the parts that people besides men played means that we are not getting an accurate picture of what the world actually looked like at those times. Over the last few decades, this has begun to change, and there are increasing numbers of important regional or individual studies that specifically highlight the role(s) and place(s) women occupied in their local societies, and the ways they exercised their agency, economic or otherwise. My project seeks to continue and expand on this work, showing the places women* occupied in different societies throughout the whole late Roman and post-Roman western mediterranean, and the parts they played in shaping the late antique and medieval worlds as we know them.

* this includes anyone who lived or identified as a woman, as far as the sources indicate