5. E. A. G. Sanderson from Barbados was the first Black student at St John's, 1889-1892

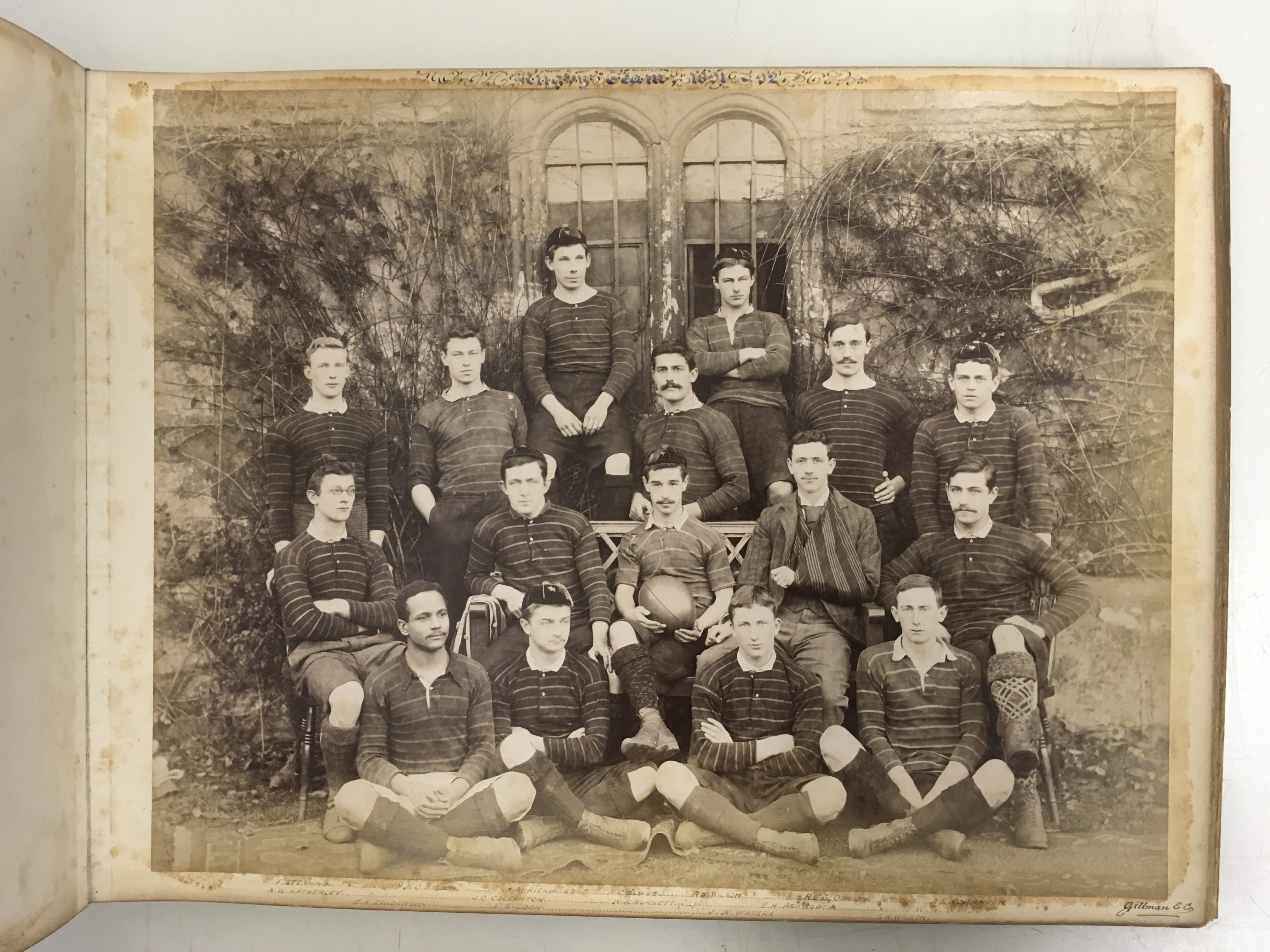

Amongst the heavy leatherbound albums of photographs of St John’s College undergraduates (the JCR as they are collectively known), this one is the oldest, dating from the 1890s. This photograph, below, is unusual amongst the pictures in these albums, for having a title above and identifying names below: “Rugby Team 1891-92” is the title written in pen on the cardboard frame.

Seated on ground the far left in the front row, cross legged, dressed in a striped jersey, long shorts and thick socks below the knee, half-coated like them in dust, Edward Ainslie Gordon Sanderson looks into the middle distance, gazing past the camera, tired after the game, or preoccupied with more pressing thoughts.

E. A. Sanderson, as he is identified below the photograph, was born in 1869, and studied at Harrison College, Bridgetown, Barbados. Harrison College is one of the country’s pre-eminent academic institutions and Alma Mater to much of its political and intellectual leadership since its founding - as a free public school for poor and indigent students by a Bridgetown merchant - in 1733. In 1888, Sanderson arrived at Oxford where he was to read (that is, study) Mathematics. He matriculated (formally entered) the University as a non-collegiate student, but in 1889 he moved to St John’s College.

Non-collegiate students could sit examinations and be granted degrees at Oxford but were not attached to an Oxford college. College membership brought access to rooms to live in, a place to eat, and a place to study, to pursue sports, make friends and socialise: the entrée to a cultural and intellectual life that is associated with the University and yet is almost impossible to access from outside a College. Non-collegiate students did not pay College fees, which are in addition to University fees; it was a cheaper option, which many students especially from outside Britain and those termed ‘colonial students’ from Britain’s formal and informal empire, were happy to take.

At St John’s College, Sanderson won two scholarships, the Stuart Exhibition and the prestigious Casberd Exhibition (‘Exhibitions’ being prizes or funding usually given for excelling in an examination). If Sanderson’s entry into Oxford as a non-collegiate student had been for financial reasons, his academic performance may have enabled him to overcome this barrier and enter the College with the help of his scholarship funding. However, the rich possibilities of College life may not have helped him perform at his best: he had a second class in his second year, and finished with a third class in 1892, though he did not take his Bachelor of Arts degree (BA) until 1901.

His birth, entry into Oxford and St John’s, two scholarships, exam results and dates until the granting of his degree: this is all that the meagre entry on Sanderson in the College biographical register tells us.

The photograph tells us a little more – that Sanderson played rugby for St John’s, for at least a year – something the College register has missed. There is very little more that we know, as yet, about Sanderson.

" This discovery in the St John’s College archives opens another chapter in a more entangled history than was known, of ever more debts owed by the College and the University to a diversity of members. "

The records of the British Red Cross from 1919 show that an Edward Ainslie Gordon Sanderson, living in 15 Lintaine Grove, Fulham, W14, London, volunteered to serve on night duty in a London hospital during the First World War; he was part of the Voluntary Aid Detachment which consisted of women and men offering volunteer help at field hospitals and medical facilities within Britain and behind the front lines in France and elsewhere. If this is the same Sanderson and he remained in Britain, we do not know what his day job was. But, between 1918 and 1919, he had spent 258 hours at Westbourne Hospital serving sick and wounded soldiers.

St John’s is not a College with strong-rooted connections with the British empire – or so it has been understood. As far as is known in the College in recent times, the earliest ‘colonial’ student at St. John’s arrived in 1892, long after the earliest such students began coming to other Oxford colleges after the 1871 Universities Tests Act removed the final barriers for Non-Anglican members of the University. Sanderson, who, from what we now know, was probably the first Black student, and very possibly the first student from Asia, Africa or the Caribbean, at the College, pushes that date back to 1889.

This discovery in the St John’s College archives opens another chapter in a more entangled history than was known, of ever more debts owed by the College and the University to a diversity of members. These members shaped the transformation of College and University in the late nineteenth century, from a still small and provincial institution with a limited curriculum teaching largely upper class and wealthy English undergraduates, into an international university producing world leading teaching and research, and made St John’s and Oxford, intellectually, culturally and materially, what they are today.