1. Joseph Lyons Walrond, alumnus and slave-owner in Antigua

We shall be posting new entries regularly starting from today and we invite you to follow the stories emerging from our research and investigations into St. John’s College’s historical connections with slavery and colonialism. From time to time we also plan to include guest blogs on Oxford and its colonial past by St. John’s students and staff and alumni as well as by friends and colleagues from within and beyond the University and the city of Oxford. This blog post is about SJC [St. John’s College] alumni who are known to to have profited financially from slavery although none of them as far as we know, gave money or other benefactions to the college.

The three alumni mentioned here, or their families, were compensated for losing their slaves (the slaves received no compensation) when, after centuries of British slave-trading, and years of struggle by British Abolitionists, the Slavery Abolition Act was passed in 1833, abolishing slavery throughout the British empire, and came into effect in 1834. We know of these alumni from an invaluable modern resource on the history of the British slave-trade – the Legacies of British Slave Ownership Database at UCL. However, it must be kept in mind that the alumni of SJC found in this database may represent only a fraction of all those alumni, Fellows or benefactors of the College who profited from the slave trade, or from owning slaves, or both. This is because we can only trace those whose names appear in the data recording compensations for slave ownership after 1833 - there may have been many others who inherited or in other ways received slave generated profits or compensation money who bore different family names or received wealth through unrecorded transactions. The SJC alumni that we know of who were either slave owners or directly profited from slavery, were Joseph Lyons Walrond (1752-1815), a slave-owner in Antigua, John Willing Warren (1771-1854), who received compensation for the enslaved people on Nantons, another Antiguan estate, and Dottin Maycock (1742-1793), Solicitor-General of Barbados who owned enslaved people on Baxter’s estate, Barbados.

This post will focus on Joseph Walrond, for two reasons: first, because he is the only one of the three for whom we have any remaining records in the College archive, beyond the bare matter of an entry of a name in the register; and second, because Walrond is connected by marriage with a more well-known slave-owning alumnus of Oxford – Christopher Codrington, who left some of his vast wealth derived from his slave estates in Barbados, as well as an enviable collection of books, to All Soul’s College, Oxford, where Codrington had been a Fellow, to build the magnificent Codrington Library. Walrond connects our research project at St. John’s with one of Oxford’s most famous, and now, infamous, buildings.

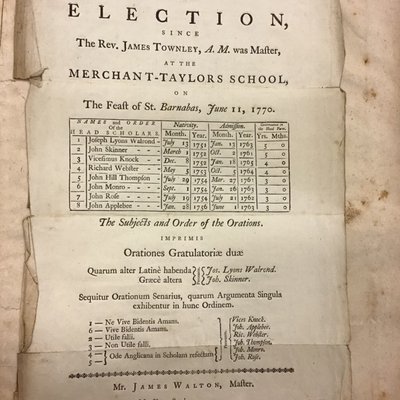

In 1770 at the age of eighteen, having tried and failed the previous year, Walrond finally secured a Fellowship to the College of St. John the Baptist in the University of Oxford. One of the few things we know about Joseph Lyons Walrond is that he attended the Merchant Taylors’ School in London. We know this because of two documents attached to the record of meetings by the College’s Governing Body, which shows Merchant Taylors' Fellows elected to SJC in 1769 and 1770 respectively. The Election list from 1769 shows Walrond’s name low down in the list, which means he did not get a Fellowship that year. However, the one from 1770, which can be seen below, shows Walrond’s name at the top, revealing that he won his Fellowship to St. John's that year. In 1770, when Joseph Walrond matriculated (was first registered as a student) at St. John’s, it was one of the smaller and poorer Oxford colleges. The College had been founded a little over two centuries years before, in 1555 by Sir Thomas White who had been Mayor of London and was a former Master of the Merchant Taylors Company (a social and religious fraternity of tailors and one of several such fraternities of artisanal craftsmen), as St. John Baptist College, in honour of the patron saint of the Merchant Taylors. It was built on the site of a former Cistercian foundation known as St. Bernard’s College.

By 1566, when Thomas White died, the college statutes provided for a President and fifty Fellows who were to be scholars of Theology, Philosophy, the Arts, and Law - at this time all members of the foundation besides the President and some of the college staff, were known as Fellows, whether graduates or undergraduates, and were not the same as those whom we would consider Fellows (academic staff) today. Under the conditions laid by its Founder, St. John’s was a ‘closed’ Fellowship. This meant that all places in the college were reserved, one could not simply ‘apply’ to the college from outside, and in any case the President and Fellows had no power to elect new Fellows: in the case of St. John’s fifty Fellowships, seven were allotted to schools in Tonbridge, Bristol, Reading and Coventry, six were reserved for Founder’s kin (related to or descended from Thomas White) but thirty-seven were for boys from the Merchant Taylors’ School and were elected each year by the School. Hence Walrond was already in a fairly good position to get a St. John’s Fellowship, by virtue of his Merchant Taylor’s background and having attended the Company’s School.

It seems likely that Walrond, was in the class of Fellows known as Gentleman Commoner. This meant he was one of a privileged class of undergraduates, paying higher fees, living in one of the better rooms in college, and taking his meals at a special table with other Gentlemen Commoners. As a Gentleman Commoner, Walrond would have given the College a piece of silver – usually a tankard or a tun (a cask or large mug for holding drink) for the privilege of being able to sit at the Gentlemen Commoners’ table. Alas this piece of silver is lost, but it might have looked something like this [see above image of Rawlinson’s cup]. Walrond does not seem to have been overwhelmed by his good fortune at getting a place at St. John’s. He remained at the college for two years before transferring to Magdalen, which, unlike St. John’s, had an open Fellowship and could accept Walrond’s bid for a transfer. Walrond went on to live in Antigua as a slave-owner, and married Caroline Codrington, whose family also owned slaves and estates in Antigua. Caroline Codrington was a descendant of Christopher Codrington, slave-owner, book-collector, and Captain General and Commander-in-chief of the Leeward Islands (effectively governor of a group of Caribbean islands including the Virgin Islands, Guadeloupe, Antigua and Barbuda, St. Kitts and Nevis). As a beneficiary under her uncle Christopher Bethell ne Codrington’s Will, she inherited enslaved people and slave estates from the Codrington family.

Joseph and Caroline’s son, Bethell Walrond, was therefore in the position, at the abolition of slavery, to claim compensation for enslaved people and estates inherited from both the Walrond and Codrington families. He became an MP (Member of Parliament) in England for Saltash and then Sudbury (1825-32). Bethell Walrond did not succeed entirely in his claims for compensation and had to surrender his Walrond estates to his father-in-law, as a part of a settlement for Bethell’s estranged wife, Janet St. Clair Erskine, though he received a share of compensation for the Codrington estates. Still, it is safe to say that he could stand the loss. Joseph Walrond’s son, Bethell Walrond’s wealth at death amounted to 14000 pounds (over one and a quarter of a million pounds today). Bethell Walrond did not attend SJC and the College’s immediate connection with the Walrond family lies with his father. However, as more and new forms of data become available we hope to search for connections between alumni benefactions and for records of the enslaved individuals and families who worked on the Walrond and Codrington estates, whose labour enabled the wealth and privilege enjoyed by both families.

Dr Mishka Sinha