3. Richard Rawlinson: benefactor, antiquarian, and beneficiary of British colonialism (Part 2 of 2)

In Part I of this post on Richard Rawlinson, we discussed Rawlinson’s wealthy, well-connected birth and origins, as the son of a prominent East India tea merchant and sometime Mayor of London – Sir Thomas Rawlinson. Richard Rawlinson’s privileged education included undergraduate study and a doctorate in Canon Law undertaken at St. John’s College, Oxford. During his university years, influenced by his older brother, Thomas Rawlinson, and a close friend of both brothers, Thomas Hearne - a well-known antiquary and Assistant Keeper at the Bodleian Library, Richard developed an abiding interest in collecting and researching old books and antiquities. We left Rawlinson embarking on his expensive and extensive six-year-long European Grand Tour. Rawlinson’s father, Thomas Rawlinson (Senior), had died while Richard was still at university. Richard’s brother, Thomas Rawlinson (Junior), as the eldest son, had succeeded to the family property and estates, while each of the other children, including Richard, were left 1000 pounds by their father.

In Part I of this post on Richard Rawlinson, we discussed Rawlinson’s wealthy, well-connected birth and origins, as the son of a prominent East India tea merchant and sometime Mayor of London – Sir Thomas Rawlinson. Richard Rawlinson’s privileged education included undergraduate study and a doctorate in Canon Law undertaken at St. John’s College, Oxford. During his university years, influenced by his older brother, Thomas Rawlinson, and a close friend of both brothers, Thomas Hearne - a well-known antiquary and Assistant Keeper at the Bodleian Library, Richard developed an abiding interest in collecting and researching old books and antiquities. We left Rawlinson embarking on his expensive and extensive six-year-long European Grand Tour. Rawlinson’s father, Thomas Rawlinson (Senior), had died while Richard was still at university. Richard’s brother, Thomas Rawlinson (Junior), as the eldest son, had succeeded to the family property and estates, while each of the other children, including Richard, were left 1000 pounds by their father.

Thomas Rawlinson Junior, a prominent book collector, had helped inspire and inform his younger brother’s enthusiasm, but Thomas’ passion for collecting also led him into irretrievable debt. Thomas spent a great deal of money on acquiring his enviable collection of books. He would often buy the same book multiple times, for the sake of acquiring a “different edition” or “fairer copy”; and so, despite having sold many books off to pay his debts, Thomas’ collection grew and grew till it filled his home at London House (a grand and many-roomed residence, formerly inhabited by Bishops of London). Thomas lived and died with his books, amidst “dust and cobwebs…in his bundles, piles and bulwarks of paper’” [Elton and Elton, The Great Book Collectors, New York, 1893, 73]. The famous eighteenth century essayist, Joseph Addison’s (1672-1719) caricature of the pedant book collector, “Tom Folio” is said to have been based on Thomas Rawlinson Junior [Addison, Tatler no. 158 (Apr. 13, 1710); The Works of Joseph Addison (New York, 1856), IV, 186-9].

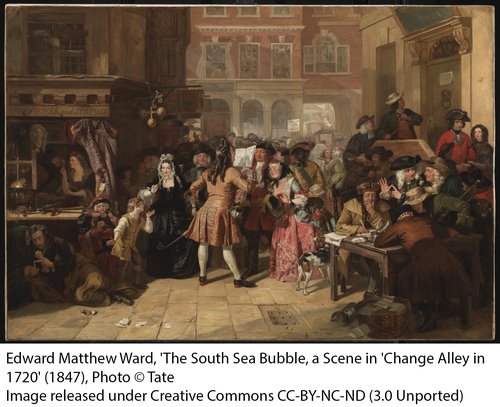

As we saw in the first part of this blog, Thomas Rawlinson had invested in the South Sea Company - a joint-stock business venture floated purportedly to reduce the National Debt by supplying African slaves to American plantations. The South Sea Bubble – as it was known, collapsed with the stock market in 1720, ruining Thomas and a large portion of the nation’s population. [image: painting, Edward Matthew Ward 1816-79, The South Sea Bubble, a Scene in ‘Change Alley in 1720, Tate Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND]

As we saw in the first part of this blog, Thomas Rawlinson had invested in the South Sea Company - a joint-stock business venture floated purportedly to reduce the National Debt by supplying African slaves to American plantations. The South Sea Bubble – as it was known, collapsed with the stock market in 1720, ruining Thomas and a large portion of the nation’s population. [image: painting, Edward Matthew Ward 1816-79, The South Sea Bubble, a Scene in ‘Change Alley in 1720, Tate Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND]

Thomas now compounded his miseries by marrying a woman from a coffee house whom he employed as a servant, at a time when such actions could and did have financial as well as social repercussions. Thomas’ indebtedness was longstanding, and though the Bubble had made things worse, his situation need not have been disastrous had he not married a woman who depleted his credit socially and apparently made him a greater financial risk for his creditors. They began to press him and demand their money back, and within a short time Thomas was financially ruined. To cap it all, the family banker - John Hannam, long-standing manager of the family finances - died in January 1725.

Richard Rawlinson heard of Hannam’s death while still on his European travels, and soon after it, of his mother Mary Rawlinson’s demise in February 1725. Richard had begun his journey back home, when he received the news that his brother, Thomas Rawlinson had died in August 1725. Richard Rawlinson arrived in England in early 1726 to find that Thomas had left a will in which he disinherited all his siblings in favour of his recently acquired wife, Amy Frewin. Richard Rawlinson was now in the unenviable position of having to find some way of retrieving the family estate while ensuring that the conditions of Thomas’ will were fulfilled – a situation that must have been unpleasant and unpalatable, especially since rumours were rife that Thomas had died from deliberate neglect or even murdered - poisoned by his wife!

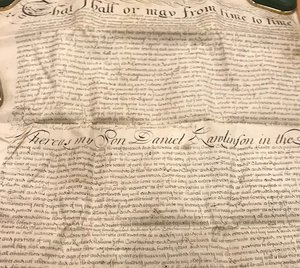

Richard Rawlinson now set himself the task – to which he devoted the next twenty-three years - of delivering the Rawlinson estate and properties from debt and restoring the family’s wealth. Deciding against challenging his brother’s will in view of the probable legal costs and length of time it would take, he chose instead to settle out of court with Thomas’ widow, who had soon remarried. Richard would pay her a lifetime annuity in lieu of her interest in Thomas’ estates, defray all debts and legacies and, for a further lump sum, be allowed to take over the administration of Thomas’ will. Hardest of all for Richard was that he had to undertake the entire process of auction-selling the remainder of Thomas’ library (still a vast collection), to pay Thomas’ debts. Having to sell a collection he coveted but had no power to possess himself was deeply galling – the more so as he had to render accounts for all sales to his brother’s widow’s new husband. Nonetheless, as the only path to financial recovery was through selling or mortgaging the real estate, and this could not be done without first settling all debts, the books had to be sold.

Richard Rawlinson now set himself the task – to which he devoted the next twenty-three years - of delivering the Rawlinson estate and properties from debt and restoring the family’s wealth. Deciding against challenging his brother’s will in view of the probable legal costs and length of time it would take, he chose instead to settle out of court with Thomas’ widow, who had soon remarried. Richard would pay her a lifetime annuity in lieu of her interest in Thomas’ estates, defray all debts and legacies and, for a further lump sum, be allowed to take over the administration of Thomas’ will. Hardest of all for Richard was that he had to undertake the entire process of auction-selling the remainder of Thomas’ library (still a vast collection), to pay Thomas’ debts. Having to sell a collection he coveted but had no power to possess himself was deeply galling – the more so as he had to render accounts for all sales to his brother’s widow’s new husband. Nonetheless, as the only path to financial recovery was through selling or mortgaging the real estate, and this could not be done without first settling all debts, the books had to be sold.

It appears that from his student days at St. John’s it had been Richard, rather than Thomas, who was responsible for maintaining the family estate and looking after family finances on his siblings’ behalf, and this role continued to be his after his return to England. As Richard slowly recovered the estate and re-established the family fortune, he was able to replenish his collections. He continued with his scholarly research and publications, though these were of course unpaid labours. From his biographical account, Richard Rawlinson seems to have been a generous friend and colleague to fellow collectors and scholars, willing to lend or share his collections, and open-handed and energetic in sponsoring the intellectual and political causes he supported. As a sibling and financial guardian however, he was severe, judgmental and ungenerous. He borrowed money from his three sisters and complained when they charged him interest. Of his four remaining brothers he got on best with the two youngest. Constantine, who had moved to Venice and relinquished all claims to the estate in return for a reasonable allowance from Richard, retained, as a result, cordial relations with him. The youngest, Tempest, helped throughout the eight years it took to auction-sell the contents of Thomas’ library, and his early death was much regretted by Richard. The other two brothers received harsher treatment, but also, to be fair to Richard, were far more trouble to him.

John Rawlinson, having quit his army career, had got himself in debt and was forced to flee London to avoid his creditors. Richard sent him to an obscure part of Cheshire, where he lived on a subsistence-level allowance of ten pounds a year – less than 1200 pounds today (National Archives currency convertor) provided by Richard, who responded to pleas for better conditions by exhorting his brother to recall his own failings and be grateful for Richard’s generosity. Richard’s oldest remaining brother had moved to Rotterdam and became a trader, but lost his money in the South Sea Bubble, fled to Flanders escape his creditors and died in 1732, leaving a wife and fourteen-year-old son, called Thomas, to Richard’s care. This Thomas Rawlinson, being the only male descendant bearing the family name, was Richard Rawlinson’s presumptive heir. He represents a further, and direct connection between the Rawlinson family and the history of Britain’s slave-trade.

Faced with the need to provide his nephew with some form of training toward a future means of occupation, Richard apprenticed young Thomas to a Liverpool shipbuilder, and hoped that when he came of age he might help his uncle by contributing to and managing the family finances. However, Thomas III (to distinguish him from his uncle and grandfather) did not fulfil his uncle’s hopes, made (in Richard’s view) an unsuitable marriage, and was disinclined to fall in with his uncle’s plans for him. In the end Thomas III agreed to give up all claims for himself and his heirs to the family estate in return for one thousand guineas with which he intended to buy and equip a slave ship to ply the Liverpool to Virginia Route. This was in 1742.

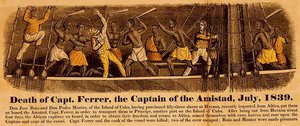

In October 1748, Captain Rawlinson’s ‘snow’ (the name for square-rigged vessel with two masts) left Liverpool with a cargo of “dry goods” for trading, bound for West Africa. Arriving in December at ‘Bonane’ - in what was known as the Bight of Biafra, in present day Cameroon, Rawlinson and his crew traded their goods and took on board one hundred and twenty enslaved people - “putting them in Irons and locking them down under Hatches” - fifteen of whom soon died “of sickness”. On 4 June, 1749 an hour before midnight, as the ship rode at anchor (probably near Antigua), the Africans rose up in revolt and attacked the ship’s crew with pieces of wood. By the next day most of the crew were dead or had jumped overboard to escape. The Africans ran the ship aground, sensibly possessed themselves of everything “worth taking away”, including the remaining crew members’ “wearing apparel” and got away. Thomas Rawlinson, who had previously left the ship with “three armed canoes” in the hope of suppressing the rebellion, had died – so it was conjectured by his remaining crew - from “Grief for the Ill Success of the Voyage”. This account of the fate of Captain Thomas Rawlinson and his slave ship arrived in a letter sent from Antigua, dated 6 September 1749, by Thomas Clarkson, the former Ship’s Mate, and was published in The London Evening Post (Thurs. 14 – Sat. 16 Dec., 1749, London).

In October 1748, Captain Rawlinson’s ‘snow’ (the name for square-rigged vessel with two masts) left Liverpool with a cargo of “dry goods” for trading, bound for West Africa. Arriving in December at ‘Bonane’ - in what was known as the Bight of Biafra, in present day Cameroon, Rawlinson and his crew traded their goods and took on board one hundred and twenty enslaved people - “putting them in Irons and locking them down under Hatches” - fifteen of whom soon died “of sickness”. On 4 June, 1749 an hour before midnight, as the ship rode at anchor (probably near Antigua), the Africans rose up in revolt and attacked the ship’s crew with pieces of wood. By the next day most of the crew were dead or had jumped overboard to escape. The Africans ran the ship aground, sensibly possessed themselves of everything “worth taking away”, including the remaining crew members’ “wearing apparel” and got away. Thomas Rawlinson, who had previously left the ship with “three armed canoes” in the hope of suppressing the rebellion, had died – so it was conjectured by his remaining crew - from “Grief for the Ill Success of the Voyage”. This account of the fate of Captain Thomas Rawlinson and his slave ship arrived in a letter sent from Antigua, dated 6 September 1749, by Thomas Clarkson, the former Ship’s Mate, and was published in The London Evening Post (Thurs. 14 – Sat. 16 Dec., 1749, London).

As promised in our last blog post, we turn now to Richard Rawlinson’s own attitude to the slave trade. At least two scholarly sources confirm Richard Rawlinson’s aversion or even opposition to the slave trade. His biography states that he “abhorred the slave trade”: one piece of possible evidence for this appears in the list of conditions Rawlinson with regard to the Anglo-Saxon Professorship he endowed at Oxford. The Professorship was endowed in the 1750s within Richard’s lifetime, but the first incumbent was not elected until 1794 (both candidates for the Professorship were Fellows of St. John’s) – not impossibly this was partly a result of the restrictions imposed by Richard. These included that the incumbent be and remain a bachelor while he held the Professorship (it was of course unnecessary to declare that he be male), and not be a native of Scotland or Ireland (Richard’s biography suggests this was for reasons connected with their support or lack of it for the disenthroned Stuarts), or – and this where it gets interesting for us - “of any of the plantations abroad”. By “plantations abroad” Richard meant slave plantations and by excluding “natives” of these, Rawlinson was undoubtedly excluding slave-owners or presumably children of slave owners from being elected to or profiting from his benefaction. Richard Rawlinson’s stance on slavery demands further investigation, and we are hoping that further information, confirming or complicating what we know, will emerge as we continue investigating the (extensive) collections of the Rawlinson family’s and Richard Rawlinson’s papers at St. John’s and other archives.

Much of Richard Rawlinson’s own papers and writings have to do with research and collection of books and antiquities and tell of his long-standing association with the Society of Antiquaries. He was also a member of the Royal Society under Isaac Newton’s presidency. Both Societies were excluded by Rawlinson from benefitting from his endowments. In the Royal Society’s case this was merely because it happened to have a closely overlapping membership with the Society of Antiquaries. The cause behind Rawlinson's bitterness toward the Society of Antiquaries lay in Richard Rawlinson’s lifelong commitment to the Jacobite cause– that is his support of the former King, James II, and his descendants, against the claims of the reigning monarch, the Protestant William III. Those who refused to swear allegiance to William III were known as Non-Jurors, and Richard’s continuing efforts in the Non-Juring cause led him to be considered a dangerous person to occupy a place in the Society’s Council. While in earlier years there had been several non-Jurors amongst the Society’s membership, as time went on this number diminished and the number of members opposed to the Non-Jurors grew larger and more powerful. In 1754, the year before his death, Richard Rawlinson was not re-elected to the Council of the Society. He responded by revoking his bequest to the Society and making the University of Oxford and his own college, St. John’s, his principal beneficiaries. In this he was also influenced by the fact that Oxford and St. John’s continued to be largely Jacobite in their political leanings.

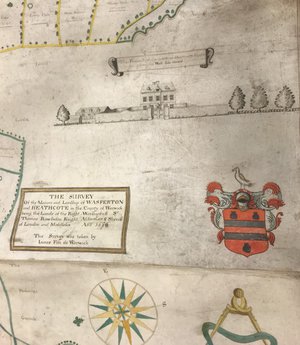

Richard Rawlinson left all his manuscripts, and most of his printed books to the Bodleian Library, but he bequeathed to his College, St. John’s, the bulk of his property, including the valuable estate of Wasperton [an eighteenth century map of the state containing a sketch of the original Rawlinson manor house is in the college archive and pictured below], several of his books, and his collection of coins and medals (now held at the Ashmolean Museum). It was the biggest benefaction the College received that century, and remains one of the largest received till date. Richard Rawlinson died in Islington, London, in April 1755. In deference to his explicit instructions, most of his remains are buried in St. Giles’ Church in Oxford, but his heart, as he had asked, was placed (in a jar) in the Baylie Chapel of St. John’s College, where it remains still.

Richard Rawlinson left all his manuscripts, and most of his printed books to the Bodleian Library, but he bequeathed to his College, St. John’s, the bulk of his property, including the valuable estate of Wasperton [an eighteenth century map of the state containing a sketch of the original Rawlinson manor house is in the college archive and pictured below], several of his books, and his collection of coins and medals (now held at the Ashmolean Museum). It was the biggest benefaction the College received that century, and remains one of the largest received till date. Richard Rawlinson died in Islington, London, in April 1755. In deference to his explicit instructions, most of his remains are buried in St. Giles’ Church in Oxford, but his heart, as he had asked, was placed (in a jar) in the Baylie Chapel of St. John’s College, where it remains still.

Dr Mishka Sinha