4. Some of St John's College's early colonial connections

The St. John’s College Register, compiled by Valentine Sillery, comprises a series of blue paper-backed volumes that together represent a significant achievement and an invaluable resource for this research project. The volumes provide a list of College members from 1660 to 1975, along with some outline biographical details. While they do not constitute a comprehensive or complete record– they remain an important starting point for our investigations into the College’s Colonial Past. This blog post introduces some St. John’s men from 1660-1775 who had a connection with the empire in this early period of the College.

The first instance of someone at St. John’s having an involvement with the empire (that we know of so far) was William Anderson. He matriculated on 23 March 1675, aged 18, the son of John Anderson of Denton, Lincolnshire, and is described as a ‘pauper’. Anderson entered service with the East India Company, becoming a chaplain. This was a critical and perilous role due to the high death rate experienced by Company employees who worked in India and elsewhere in Asia, caused by a combination of tropical climate, fatal diseases and unhealthy lifestyles (i.e. excessive drinking). We do not at present know anything more about Anderson’s colonial career, but further research in the Company’s archives in the British Library in London may yield further details. On 15 July 1693, John Cooke matriculated from St. John’s College. Cooke was the son and heir of Sir Thomas Cooke, a goldsmith and Deputy Governor of the East India Company. John did not follow in his father’s footsteps, instead taking to the legal profession. He was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn in 1694.

In the 1720s we begin to see (English) men from Britain’s colonial possessions in the Caribbean arrive at the College. One of the first of these was William Dowding or Dowden, who matriculated in 1724 aged 19 - the son of William Dowding Senior who resided in St. Michael, Barbados. Dowding remained a Fellow until 1737 when he ‘resigned, from Barbados’. John Skinner matriculated in 1770, but resigned after a year. In 1773, he joined the 16th Regiment and ‘served with distinction in the West Indies’. During the Napoleonic Wars he was Governor of St. Martin (Martinique) in 1810 and Guadeloupe from 1812 to 1816. He rose up the ranks to become a Lieutenant-General in the British Army in 1821 and died six years later. Theophilius Field, from Antigua, entered the College in 1724. He appears to have returned to Antigua as there is a copy of his 1736 Will in V.L. Oliver’s three volume History of the Island of Antigua (1894). Ballard Beckford arrived at the College from Spanish Town, Jamaica, in 1726. He returned to Jamaica, became a ‘merchant and councillor’ and married Mary Clarke, daughter of the Governor of New York. He died in 1760.

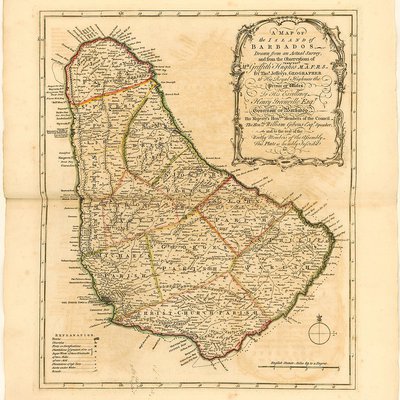

Perhaps the most famous alumnus of St. John’s who lived and worked in the Caribbean was Griffith (or Griffin) Hughes, who matriculated in 1729. Hughes was appointed Rector of St. Lucy’s, Barbados in 1736, remaining there until at least 1748. During his time there Hughes began researching the natural history of the island and conceived the idea of publishing a book on the subject. In 1743, visited London to promote this object, meeting leading scientists of the time and successfully soliciting their support. In 1748, on his return to England, Hughes was made a Fellow of the Royal Society and received his BA and MA degrees from St. John’s. Hughes’ magnum opus, The Natural History of Barbados was published in 1750, an opulent folio production with several coloured plates by the well-known botanical artist Georg Dionysus Ehret, an engraved map of Barbados by Thomas Jeffreys, Geographer to the prince of Wales, and paid for by a list of a thousand subscribers including the King, and Prince and Princess of Wales. Hughes’ book did not receive universal acclaim on its appearance, being described as inaccurate and lacking scholarship by fellow scientists, however it did achieve a number of firsts. In his book, Hughes provided the earliest description (in English) of the grapefruit - which he called ‘the forbidden fruit’, and coined the term ‘yellow fever’, although the association of that disease with mosquitoes came much later. A copy of the book in ten volumes is held by the Royal Collections Trust and scans of its exquisite plates may be seen on the Trust’s website.

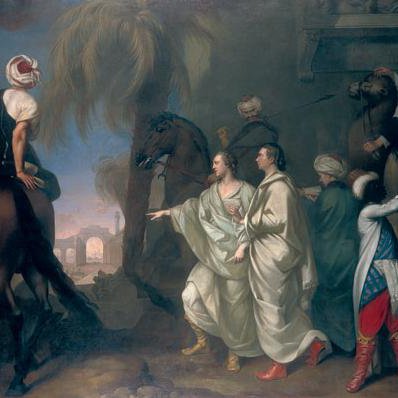

James Dawkins matriculated on 7 December 1739 and was granted an honorary DCL in 1749. He was the eldest son of Henry Dawkins, of Clarendon, Jamaica, a wealthy sugar planter, and his wife Elizabeth Dawkins née Pennant, daughter of Edward pennant, Chief Justice of the island. Dawkins was heir to a considerable inheritance, and owned 25,000 acres in Jamaica with his brother Henry Dawkins, a plantation and slave owner. His wealth provided James with the means to indulge his two interests: archaeology (or antiquarianism) and Jacobinism. During his travels in Europe Dawkins helped James Stuart take measurements of the remains of Ancient Greek architecture in Athens. Dawkins’ main achievement was his role in the discovery of the remains of Palmyra and Baalbek in Syria. Dawkins planned the expedition, which was to be around the Eastern Mediterranean to the sites of Classical antiquity, with an Oxford friend, John Bouverie in 1749. They were joined by Robert Wood, a classical scholar, and Giovanni Borra, an architectural draughtsman, though Bouverie died before they could complete their journey. They arrived in Syria in March 1751. With Dawkins’ financial support, Robert Woods published The Ruins of Palmyra (1753) and The Ruins of Baalbec (1757), containing detailed engravings of architectural remains, that were entirely new to the books’ Western European audience. Dawkins also helped finance James Stuart and Nicholas Revett’s even more influential book The Antiquities of Athens (1762). A collection of manuscripts and another one of marbles from Dawkins’ travels are held at the Bodleian Library and the Ashmolean Museum respectively.In 1753, James Dawkins was involved in a Jacobite plot with Dr. William King, Principal of St. Mary hall, Oxford, and the Earl of Westmoreland. The British Government issued a warrant for his arrest which was not executed and did not seem to harm his political career: in 1754, Dawkins returned to England, bought an estate in Hampshire and was returned as the Member of Parliament for the open borough of Hindon, Wiltshire.

John and William Morant were two brothers who matriculated in the same year, 1741, when they arrived from Jamaica. Their father, John Morant, had a bay named after him on Jamaica, which became notorious as one of the sites of the Morant Bay Rebellion in October 1865, which was brutally suppressed by the British. James Langford Nibbs was the son of James Nibbs, a ‘gentleman of Antigua’. But James Junior does not seem to have returned to the island, as he moved to London in 1758 and then to Beauchamp, near Tiverton in 1791. Finally, Richard Iles arrived at St. John’s from Montserrat in 1766, became a member of the island’s Council in 1774, and served as President of Montserrat from 1792 to 1798.

As this blog post has shown, there was a small but steady trickle of men with colonial connections who were Fellows or otherwise studied at St. John’s in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, most of whom were connected with Britain’s Caribbean colonies. These are only short biographical sketches, but further research will hopefully uncover more about these men’s families, their lives and careers, as they were shaped by their engagement with colonialism

Mishka Sinha, Oxford, 28 July 2020